Pernilla Winberg, ’Not Let Me Go,’ 2021. Commissioned by Cero Magazine.

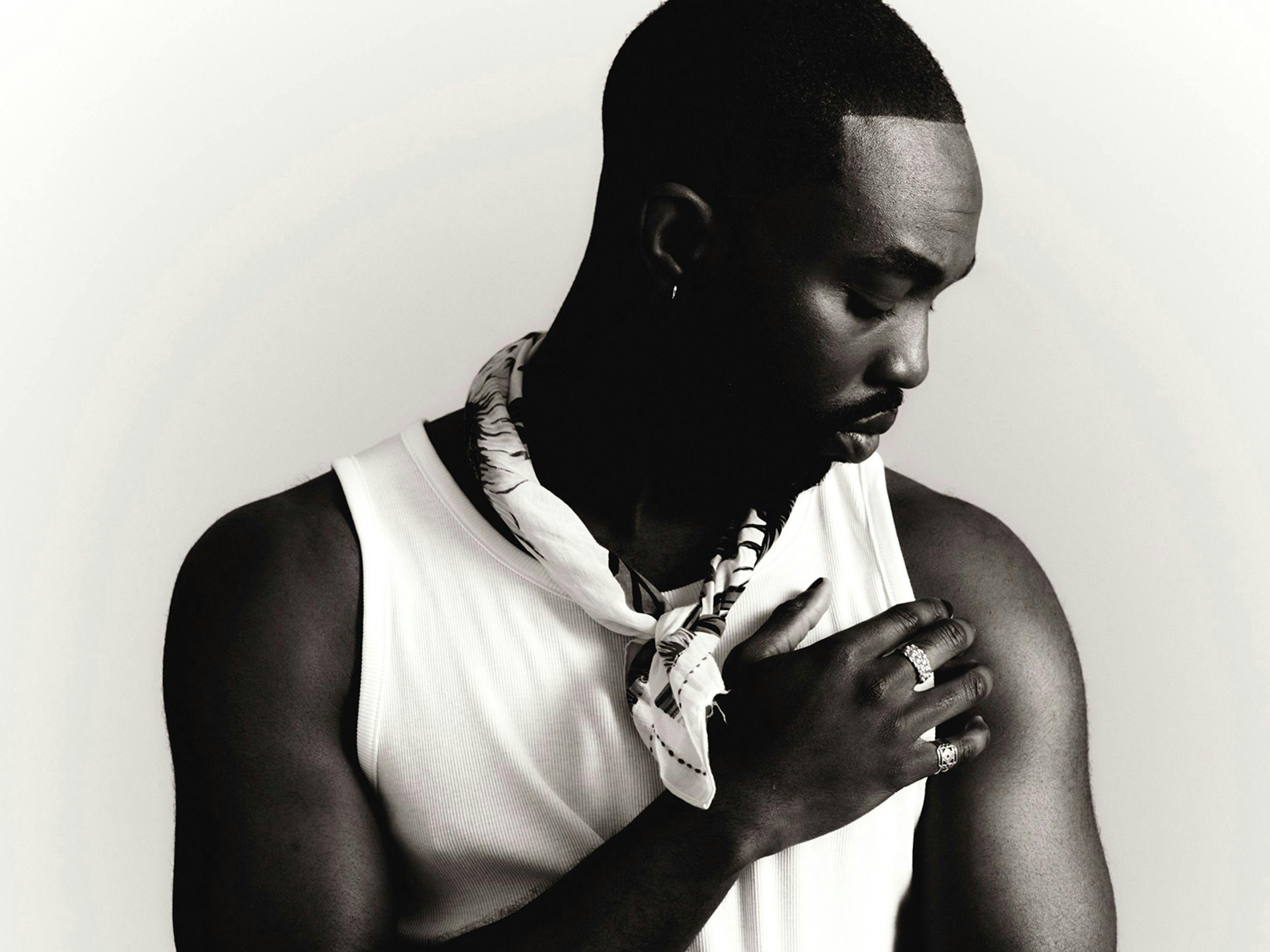

A Place With Many Doors

She died like death meant nothing to her. Even forgot to close her eyes. As if she could—wanted to—see everything around her. But her thin legs that had been flailing in the air and the delicate hands that had been clawing the ground, gathering dirt under her bitten fingernails, stopped moving, and he knew she was dead. That did not stop the man, whose face was crunching up as if he was in pain and who then, as his foaming mouth opened, let out a guttural groan while he shook like he was possessed by a legion of demons. The others stood around and cheered him on, grunting, chanting incoherent words meant to inspire pride in whatever they had done; satisfied by their violent, vile deed.

They were not supposed to kill the girl with the big brown eyes and skin the color of dirty leather. They were not supposed to. But they said the man’s victory in the elections had been stolen for the third time, and also she was from the wrong tribe. What was she doing there anyway? So they took turns at her—all seven of them—and when she was too tired to fight, and no sound was coming from her parched throat, the one with the crunched face took a rusty machete and cut her throat, not considering the fact that she had died long before he was done.

The boy was not supposed to be there, but he saw it all. His stomach turned as if his intestines were being knotted by a skilled weaver. And he knew if he retched from the metallic taste in the back of his throat and vomited they would find him behind the tower of garbage and cut him up into tiny pieces of meat. Like the cow meat at the butchery.

Or maybe, because he was from the right tribe, they would have told him to run home and tell no one. But he didn’t make a sound. And after they left, he walked over to the girl and told her that he was sorry as if he was the one who had done it, and that’s when she closed her eyes. He said he was sorry over and over again, expecting her corpse to have a heartbeat, a pulse, start breathing, stop flailing her legs in the air, stop clawing the dirt, get up from the ground, shake the dust off her hair, open her mouth, and tell him, “You are forgiven.“ It did not. Eventually, he walked away and left the dead girl’s body there. He put the back of his hand to his face and wiped away the tears from his eyes as though that alone would wipe away what he had seen.

He never told anyone what he saw. His eyes had stared into a darkness that he could not capture with words. Not even when he got home, and his mother, who was sitting on the floor with her legs stretched in front of her and her palms rubbing her thighs in slow circular motions, told him that the girl’s mother had taken off and left her shop open for them to do as they pleased. He was going to ask his mother if they did, but she was already calling his brother to go and fetch water for the chang’aa. No one knows where or when (if) the girl’s mother stopped running. All over the country, they were doing the worst to young girls, old women, children, and old men, and the whole country was like a hyena that was eating its own children and accusing them of smelling like goats. But then the two old men who had been fighting over the seat showed up on TV and shook hands and the whole country paused, arms mid-air ready to hit, and said, “That was bad.“

---

The first time she came to him, he thought it was an apparition, a consequence of his imagination. And yet, he could feel her presence in the room, engulfing every inch of the stuffy house he shared with his five siblings. Her scent clung to the air and with every breath he took, he felt as if he was inhaling her and she was taking over him. How could this be, he wondered, when she died exactly ten years ago? It had been ten years and she and all the other girls had become nothing more than songs whose words had been forgotten—lost—to everyone else, remaining only as tunes hummed when the nights were cold and the children could not fall asleep.

But then she came, bones and flesh, she came. Her head was no longer falling off her body and the red was not spurting from her neck like the gush from the neglected burst water pipes. Her hair was not tearing off her head from all the grabbing and pulling. Her skin shone, glowed when the sunrays fell on her. Her dress was not torn and the only stain on it was from her mother’s lipstick she had stolen the day they were to meet. She was whole, just as he remembered her from childhood. Except she was grown. The body of a girl who was fast becoming a woman. Her face still looked just like the face she wore when he was thirteen and she was eleven. Like she did on the morning when she came to their window and peeped and said, “They have started counting the votes.“ His mother never liked her habit of holding on to the window rails and lifting herself up until her toes pointed and sunk into the soft earth. “Are there no doors where they gave birth to you?“ she would say to her. And she would squeal and retort, “There are so many. Even doors that lead nowhere.“

The boy always wondered where she was born.

A place with many doors meant that one was free to come and leave at will. It meant that doors were always closing and shutting, creaking at their hinges and clicking in the locks. He had always wanted to stay in such a place, and not this room with one door that had belonged to his great-grandmother, his grandmother, and now his mother. Imagine living in a place where one door led to another and another like there was no one to bark, “Don’t leave that door open, boy!“ in the way his father used to say before the disease came to him and took his throat, leaving him with nothing but the mere whimper of a puppy. His mother said it was because he drank all of her profits, but they all know it was something more, a dangerous kind of fire that reckless men swallowed from the building down at the secluded part of the town. Anyway, the day came and life closed its door on him.

Did the doors of heaven close on her, locking her out, and that is why she was here?

On the day she came to him, he was preparing the pots for the boiling of the millet and sorghum. His two brothers had taken the wheelbarrow to go fetch the water and his eldest sister was busy trying to save her fifth marriage. When she appeared, he wanted to scream but then he saw she was whole and grown and he thought maybe he had imagined her death ten years ago, an imagination so elaborate and complex it was, essentially, to him, the truth. He smiled and she returned his smile. He folded himself in her open arms and her embrace was so warm he wanted to stay that way forever and never leave. They were that way for a long time until the baby’s cry split into the moment, lodging itself between them. He opened his eyes and withdrew from her embrace sharply, quickly as one withdraws their hand from a flame. That is when he saw the betrayal in her eyes.

The baby’s cries rose and rose, and he wanted to turn and go pick it from the large bed, but he thought if he left the spot he was standing in, he would turn to find the girl gone, vanished like she had appeared. Therefore, he stood there until she asked him, “Are you not going to take your baby?“ The question was deliberate and he tried reading her face to see what she felt but she gave him nothing. Her voice was as clear and shrill as he remembered it. It made him remember all the songs she used to sing to him in a language he never understood. It made him remember—the baby was crying. He turned and picked up the baby from the bed, and when he turned back again, expecting her to be gone, he found her there. Standing with her arms still stretched in front of her, like how they had been.

They stood there, facing each other, and for a moment, he considered he was imagining things. Yet, she felt as real as the baby he was holding in his arms. He wanted to reach over to her again, close the gap between them and fill up the years when she was not there. He wanted to put the crying baby down and have his hands free so he could hold her. Standing there, barely ten meters from him, she looked so alone, so lonely. The realization that this loneliness could have been her life for the past ten years made his insides swell with shame. Yet, here she was. Back. Wherever she had been, whatever she had been through, he was going to make it right by her.

“She is such a beautiful baby.“ Her voice, low and piercing.

“He. He is a boy.“ He let out a nervous laugh that did not convince him.

“Boys are trouble. Beautiful boys are demons.“

“He is just a baby. Don’t say such things.“ He had not meant for his tone to be that sharp and defensive. He wished he could unspeak the words, swallow them back into his stomach. But they were out there already, and he hoped she did not take it to heart.

“Mothers are meant to be with their children.“

He wanted to tell her that his sister had left the baby with him so that she could go find her husband in whichever brothel he was calling home or whichever chang’aa den he was spending his days. He did not. She stood there, staring outside the window, past the clothing lines with wet dripping clothes, all the way past the mountain of garbage with the children dancing on top. He could not see what she was looking at, but he knew the shirtless children dancing to made-up lyrics of Awilo Longomba’s songs were not objects of her fascination.

“What do you see?“ she asked him. The question caught him off guard. He hesitated, straining to look past her and see what she was seeing. The heat from the sun burned his eyes and the baby’s low, muffled cries with hiccups that sounded like the pop of gum could not let him focus.

“Nothing,“ he responded, feeling defeated.

“Those children up there, do you think they see what we see?“

“What do we see?“

She did not respond. Her large eyes darted, sweeping the side of the room she was facing, then stopped again outside the window. Her frame was rooted to the same spot she had appeared. He wanted to move closer to her, touch her, and let her know that he wanted to see what her eyes were seeing—what the children could not see.

“The children, they don’t see the hate in us. They are unable to.“ Her voice startled him in the way it was brittle and sharp like cut, unsmoothened glass. The baby had stopped crying and his head rested on his shoulder. He stared at the children dancing in the blazing afternoon heat without a care.

He remembered when they were children.

She, two years younger than him, but faster and quicker than anyone he knew. She outraced him, even when he started running when she was still saying, “On your marks, get set—,“ and his body was already tearing through the blazing heat, his shirt flailing behind him, his torso stretching and hurting, his legs pulling and pulling, the weightless feeling of joy, pause, then the fatigue grinding at his bones, pause, the wind slowing him down. He would start gasping for breath, and that is when she would dart past him like an arrow shot from an eager hunter’s bow.

When they were children.

The children did not see them. They danced, their waists and legs becoming rubber becoming water becoming air. Their hands were unable to hold them, and the sound of the paint containers being hit with the thin sticks was what filled the air. They sang. No coordination, no harmony, no nothing except the blissful innocence of childhood. That is what he missed most.

The baby slept through it all. Burped once or twice, snored softly, dug his small head in his neck, did everything a child does when they sleep. He stood there with her, careful not to say anything that would make her leave. Careful not to hurt her again.

“Do you remember when we were children?“ he asked.

“Everything about it. It is the only reality I know. The only one I live.“

“Were you happy then?“

“I suppose. But sometimes I wonder if I even knew the true meaning of happiness back then. Was I conscious of it? I wonder.“

“Are you happy now?“

“...or if I was confusing it with something else. Some other emotion?“

“Grief?“

“I am incapable of being happy now. I cling to the moments in my childhood.“

“And grief?“

“What about grief?“

“Those children.“ He turned towards the window and the children had melted to nothingness; going, gone. The haze of the afternoon heat no longer danced. The wind blew gently from the lake. They were gone. They had disappeared. He would see them again, he knew, for they had made a home out of that heap of garbage, spending their days clawing through the used condoms, soiled Pampers, polythene bags full of dog vomit and children’s runny shit. They dug through, trying to find bits of metal to sell to the scrap dealers. Did they know anything about grief?

“Sometimes your entire life is a long, continuous episode of grief.“

He did not listen to her, ignoring the words she had spoken. He trained his eyes and mind on the children. On their absence. The huge pile of garbage with flies buzzing around. With cockroaches roaming, searching, and being the filthy insects they always were—are. The sound of the street was the trill of a cricket. A prolonged sound that hurt the ears and calmed the mind.

It was almost evening. His sister, if at all she was coming back, was bound to find them standing like this, motionless in the middle of the living room. She would have asked, “Brother, have you lost your mind?“ her high, booming voice scattering his thoughts, and perhaps even her presence. She must have sensed his fear and she turned to him, her face glowing in the orange light of the sunset, and she told him, “You and I have work to do. I will come back at dawn.“

“Where will you go?“

She was gone.

Pernilla Winberg, ’Hold My Hand With Me,’ 2021. Commissioned by Cero Magazine.

The man in the green jumper took three steps forward, two steps back before his knees buckled and he folded like a thirsty camel. He was the first to go. And while everyone stood around and watched while saying, “Omera, let’s get this guy to the hospital,“ he already knew that he would not survive what she had done to him. What she had made him do. He squirmed and wriggled on the dirt like he was a large headless snake. He was in so much pain. He tried to block the screams out of his head, but the incessant ringing that the screams left made his head hurt. He turned away from the crowd, and even though all he wanted was to get home and wash his hands, she made him turn back and forced him to look.

“He did worse to me.“

“I was there. I saw it.“

“You didn’t stop them!“

“Is this your way of punishing me?“ He repeated the question over and over and over until it replaced the man’s screams, the eclipsed voice becoming faint with every boom of his own voice. He heard himself, the clarity in his voice, as if he was in a large empty room with closed doors and windows; the echo of pain mixed with something, something he didn’t know how to name yet. He asked the question again. He already knew her answer: “You were just a child back then.“ That would have been her response. She had not said anything to him, but he understood that even without her telling him certain things, he could know them.

Like the day she had told him to find the man in the green jumper. He was not wearing a green jumper when he found him, and his face was no longer crunched as he remembered it; creases and folds ran all over it, and he knew, even then, that time and sadness had converged there. He observed his face, taking in his eyes that had the color of marbles when hit with light at the right angle. He watched his mouth as it opened, his chapped, reddened lips parting ways, for the ball of ugali to get inside. He hated him. He walked over to him and stood over him like he was some god.

“Get me ugali sosa.“

“I don’t work here.“ His own voice sounded different. It was still his own.

“Then get away from me.“

That is what made him the first to go.

This is how he went.

He followed him from the restaurant and knew where he lived. He went back home and found her seated there waiting. When she asked if he had found him, he simply nodded. She smiled and told him he had to do it. She made him remember how he was the one who cut her throat like she was just some chicken. And when she was done, she told him he owed her this. And he nodded again and again as if to say he understood.

The deed was simple, a knife to his throat, blood spilling like water from a fountain, sound struggling to come out. Red, red, red. He looked in his eyes when he held on to his throat and walked outside the house, his neighbors seeing him and suggesting he be taken to the hospital.

That is what she did. That is what he did.

---

He realizes now what he did not know back then, that human beings change. Sometimes, for the better. Sometimes. Other times, however, they change for the worse. Not entirely but they become capable of actions that make one say they have changed for the worse. And that is exactly what he thought of her after that first time. After she made him do what he did to that man in the green jumper. As he washed his hands, scrubbing with all the rage he could muster, seeing the water take on a new color, he shook his head and the pain was unbearable. He wanted to shut it out. It was as if, in doing what she had made him do to the man, the pain had bounced back and hit him with more impact than he had used on the man.

However, she was not done yet. She made him follow the man with one bad leg who wobbled when he walked, the short man with skin black as tar, and the wiry man with eyes that looked in opposite directions as if they had had a disagreement when he was a child. She made him find them, follow them, and do to them what she had made him do to the first man. All of them cried and howled when it happened. All of them died a death filled with so much pain, a certain kind of pain that reached the depths of the flesh and yanked away everything that mattered. All seven of them, eventually, one after the other.

And when, three weeks later, she told him she was done, he shook his head and fell down with exhaustion. He woke up on the bed in the house right next to the baby, a paste of his vomit covering his face. He turned towards the door and saw her standing there.

“What more do you want?“ he moaned.

“This is not what I imagined it would feel like.“

“Have I not given you your revenge?“

“It feels empty.“

“That kind of hunger and hollowness cannot be sated. It yearns for more always.“

“More? Of what?“

“Of what you fed it the first time.“

He got off the bed and walked towards her. She seemed terrified, like she was the day the men came for her. Like she was when they pushed her to the ground. He touched her face and she was cold. He withdrew his hand, turning his face away from hers.

“Why did you come?“ It was only now that he thought to ask her the question.

“I had to at some point. My return, and that of all the other girls the world scarred, was inevitable. We were not going to let our songs be silenced. Our fires would not be extinguished.“

“But after all this while? Why now?“

“We lurked on the other side for so long, groping in the dark, scared, weary. We watched through the glass how the people who hurt us went on to hurt more and more people—young girls, little boys, frightened mothers. We watched. We screamed. We wanted to leave but there were no doors. You couldn’t just walk away like it was a house. We screamed louder each day, our anguish growing into a song that chorused and swallowed everything. And at some point, our screams became loud enough that the glass shattered. Some of us crossed. Some of us were too tired to cross.“

“The world burns and burns, charring even its own children.“

“We ourselves burn the world.“

She walked closer to him. He could feel the ice of her breath on the nape of his neck. He felt weightless. He wanted to turn and face her, but he did not know what he would see in her eyes. In that moment, the door creaked open and his sister and her fifth husband rushed in, shouting expletives at each other. Eleven months they had been together, the longest he had seen them. That was two months more than she had been with her previous husband. This one, she had sworn she loved with everything she held dear. She had once told him that she would die if he left her for another woman. Now, however, she called him a smelly cockroach, a wild dog, a crippled donkey, and all the other names she could. It was over this time. She picked the child from the bed and when he started crying, she handed him over to her husband. Yes, it was over.

He stood there, watching them but not seeing, as if his vision was fading. The baby cried louder and louder until he could not hear himself think. Still, he ignored the crying and the shouting and stood there, transfixed to the point she had left him. He listened. He listened to the sound of the girl going away. He listened, for something in the way her feet sunk into the ground. He wondered if she would ever come back.

Troy Onyango is the founder of Lolwe, a literary magazine focused on African authors. Read this story and many more in print by ordering our third issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.