Amoako Boafo, Phase V - GOLD EARRING, 2024

Amoako Boafo’s Portraits Look Beneath the Surface

Of all the journeys we take in life, the romanticized life path that leads to creation—the artist’s way—is often indistinguishable, much like any other. Like anyone, artists are born, sooner or later face challenges; they navigate obstacles and make decisions that reflect their needs and wants. In the best cases, however, artists are afflicted with a pathology that can override logic, rationality, and tradition.

Amoako Boafo, White Pearls, 2023

My understanding of true artistry was best described by the brilliant, late writer Toni Morrison. For many years, she taught the techniques of writing that structured her prolific career. Most notably, she did not believe that passion or vision could be taught but lay in that most incessant curiosity and the obsessive exploration of what is or is not. “There is such a compulsion to it,” she mused, “that anything else that I’m doing looks as though it’s underwater, and then there’s this dazzling thing…” Art is so infrequently an adequate catalyst for living and making art. More often, it is a necessary tool on the journey of life. But the most compelling artistic journeys, it seems, are those that reveal an overwhelming desire to understand the nature of life itself, indeed why we’re walking any path at all. Such compulsion corrals artists toward a life that revolves around art—to continue revisiting age-old questions in hopes of provoking new answers.

Amoako Boafo, Thick Black Hair, 2023

Such aspects of artists’ lives, call them craft or process or invention or meditation, are always subject to shifting theoretical fascinations. Amoako Boafo, a forty-year-old Ghanaian painter, displays a sincere commitment to his own explorations of representation, despite growing critiques of the genre of Black figuration. But while many of those critiques may hold true when considering the entrenched racial politics of the art market, Boafo’s individual meditations on the indescribable essence of personhood present an undeniable defense of the value of representational images. “My paintings are always more than just visual representations of people,” says Boafo. In focusing on emotional depth, his portraits are not easily interpreted as documents of people in the world at a traceable place and time: “I try to capture the essence of individuals…and so there is always a fusion of both reality and artistic imagination.” His works are not portraits in an archival sense—a clear contrast to works by comparable contemporary Black artists such as Kenyan-born Wangari Mathenge, and even the younger American painter Gerald Lovell (who, like Boafo, has taken up a profound usage of impasto techniques to render the rich texture of dark skin).

Amoako Boafo, Labios entreabiertos, uñas blancas, 2023-2024

The centering of painting in Boafo’s artistic practice has become a vehicle through which he experiments with the possibilities of picture making, all the while probing what is integral to such representations. Boafo’s question, however, is not a challenge; the realist image has been challenged to destruction and reconstruction for nearly a century or more in numerous visual cultures globally. Nor would he readily embrace the work as a grand political statement. Rather, in addition to many other art historical and theoretical fancies, Boafo’s present body of work is perhaps best understood as the output of a beautifully persistent line of inquiry, a fascination that seems to drive the artist’s practice.

Amoako Boafo, Cuello amarillo, 2023-2024

Creating works in his distinct way, he creates pieces that he describes as going “beyond mere replication, offering viewers a glimpse into a world,” a world in which certain additions to and subtractions from reality are articulated in bold patterns, white space, hyperreal textures, and the subtleties of expression. Often described as semi-abstraction, in the last few years these techniques have resulted in paintings that appear to isolate their subjects from the world they inhabit. In this way, Boafo’s finished works rely heavily on ambiguity: “I value the element of mystery, occasionally opting for anonymity, allowing viewers to interpret the art through their own unique perspectives.” For Boafo, it is essential to invite viewers’ personal interpretations and connection into each artwork. “By keeping subjects unnamed,” he shares, “I not only safeguard their privacy but also invite viewers to explore the artwork without preconceived notions, fostering a more uninhibited and intimate engagement with the piece.”

Amoako Boafo, Phase IV - COFFEE BROWN, 2024

This level of anonymity has almost always been a useful tool for painters of marginalized and increasingly at-risk subjects, though the apparent likeness of Boafo’s subjects can be deceptively inaccurate if one is looking to identify a particular figure in the artist’s circle. While he often draws inspiration from individuals who have touched his life, many of the figures are composites. “Some of the figures in my pieces are rooted, while others emerge from the realm of imagination,” and because the figures are most often unnamed, or vaguely so, the line between the eidetic (a type of vivid mental image, not necessarily derived from an actual external event or memory) and the real is indiscernible to everyone but Boafo. Though these kinds of images are often perceived to be confusing, frustrating, and at times idealistic, I would argue that for artists working in this style, the lack of specificity is equally a tool of self-exploration, acting in a fashion similar to Rorschach drawings.

Amoako Boafo, Phase III, ELINAM, 2024

Ironically, it is Boafo’s sizeable body of self-portraits that exemplify my associations most clearly. Recently on view as part of the artist’s debut US solo exhibition tour, “Soul of Black Folks” (Denver Art Museum), Boafo’s self-representations, such as Black Skin, White Masks (2016); Ghana Must Go (2017); and Reflection I (2018), depict the artist as his subjects are usually seen, commanding the space they inhabit. “My self portraits aim to convey a deeper understanding of my identity, experiences, creative process while offering a more intimate glimpse into my inner world that shapes my artistic vision,” he shares. His vision, in this context, is informed by important works of postcolonial literature from the Black diaspora including Frantz Fanon, Taiye Selasi, and WEB DuBois. The exhibition title takes its inspiration from DuBois’s 1904 publication Souls of Black Folk, though removing the plurality from the word ‘soul’ could indicate that Boafo sees in DuBois a unifying call—if not in the text itself, then in the possibility of his own work. “I am interested in connecting, exchanging, and learning from the diversity across the diaspora as it relates and expands my understanding of myself and home,” says Boafo. He also admits that he sees DuBois’s theory of “double consciousness” as a way to understand the way he moves through the world: “It’s a theory that helps me understand the way a society’s politics, culture, and social norms impact my work and how I am perceived. As a Ghanaian artist, when I travel across the US and Europe for work, and as my work travels around the world, I become more aware of the power dynamics within society.”

Amoako Boafo, Phase II - TASIA,2024

But alongside all that the titular texts communicate about the artist, they also remind viewers that the process of artmaking is always first and foremost a journey through the self. The mirror image, as seen in Reflection I (2018), serves as an æsthetic fascination, while exploring the intimacy of such reflections and all they inform. “When we gaze at our mirror image, we are faced with a direct visual feedback that draws us into an interaction between a fascination with our external appearance and self-reflection into the deeper layer of our identity,” the artist says. Yet even when focusing his attention outside of his reflection, Boafo’s self portraits imply a deeply rooted interest in “contemplating the interconnected nature of individuality and shared human experiences,” and inviting viewers to do the same.

Amoako Boafo, Phase I - AYANA, 2024

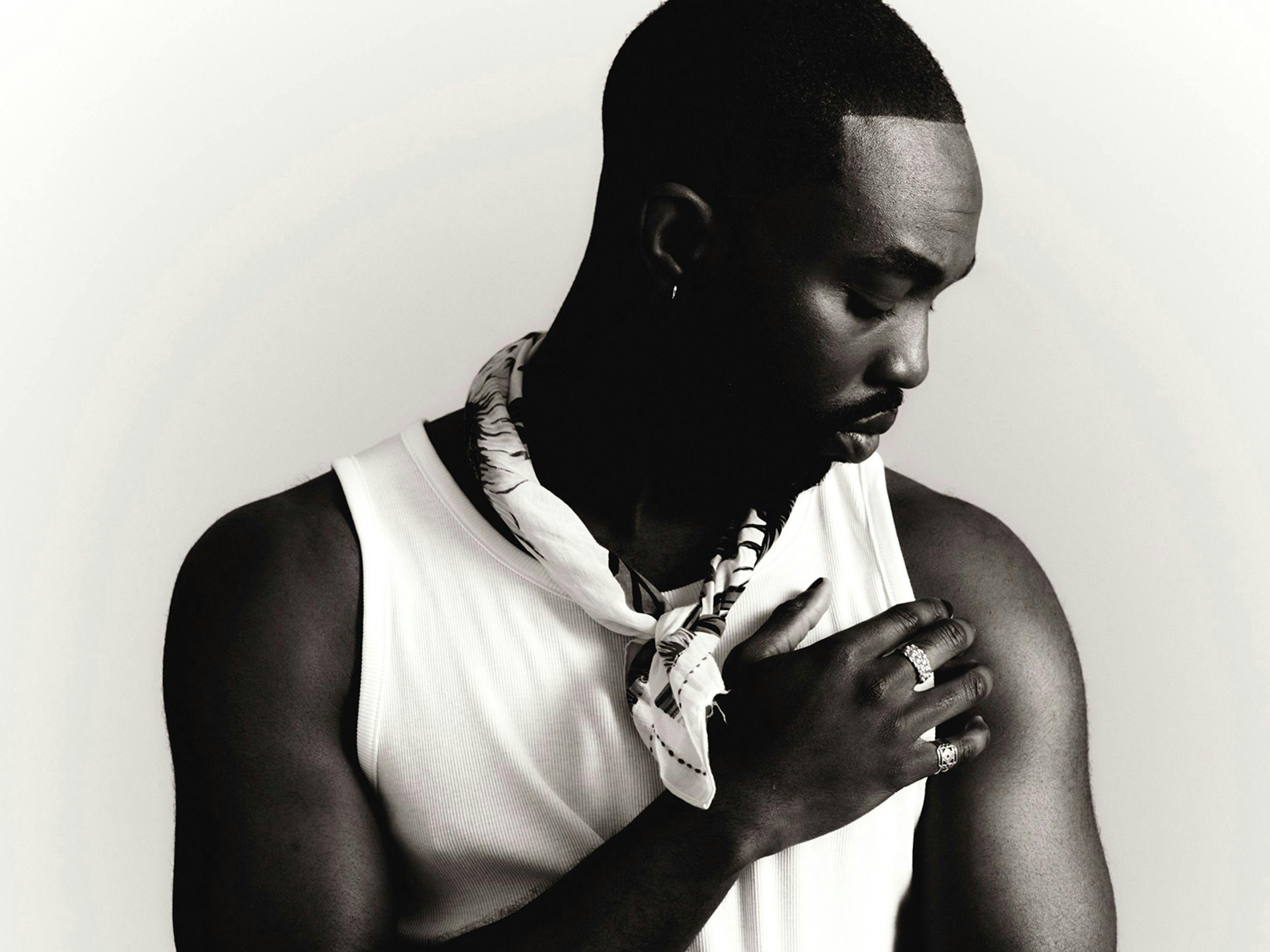

Amoako Boafo, Artist Portrait, 2021. Photo by Nolis Anderson.

These earlier self portraits, along with Boafo’s present experiments in collage and stained glass, evoke an unspoken intimacy with the self and others developed through the path of artmaking. Looking inward, Boafo has developed a pictorial intimacy through self and material reflection, intensifying the textural sophistication of his paintings by using his physical hand more readily to apply paint to his representations of figures: “I wanted to see myself in the works and make sure other individuals from the diaspora could see themselves in the pieces.” The works displayed at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery in Mexico City earlier this year as part of “The One That Got Away” contain traces of the artist’s own artistic identity and intimate connections to figures real and imagined. “Exploring stained glass and mosaic techniques has only broadened the horizons of what my paintings can express,” he says. The new venture, Boafo states, is more than a form of iterative experimentation in a representational medium but also an invitation to collaboration which “adds an intriguing layer to my creative process.” The opportunity to make and view works with an even greater expression of physical interconnectedness is a welcome experience for viewers as much as it is for Boafo.

Amoako Boafo, Sponge Bob Boxers, 2024. Photo by Ramiro Chaves.

As someone who began his artistic journey in Ghana, followed the legacy of Egon Schiele to Vienna, and now faces a sense of relative isolation from the intimacy of the diasporic community, today Amoako Boafo has shaped a life and artistic practice grounded in the æsthetic intimacy of Black representation. “Rather than deter me, this prospect intrigued me,” he shares of his time at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. Despite facing challenges along the way, he did what most artists must to occupy a position like his in the global art world—follow his authentic path. Especially at a time when many Black artists and audiences are abandoning representation for more ephemeral, conceptual practices, Boafo remains steadfast in his pursuit: “I do not see it as something to move on from because it’s ‘no longer serving a perceived purpose.’ On the contrary, I find it even more exciting now as I get to know and try to understand humanity a little bit more. All I can say is for now my practice is about figurative representation.”

Read this story and many more in print by ordering our eighth issue here. Boafo has selected dot.ateliers, a residency program under the dot.arts foundation in Accra, Ghana, as the recipient of proceeds from direct sales of CERO08.

Amoako Boafo, Top halter blanco, 2023-2024

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.