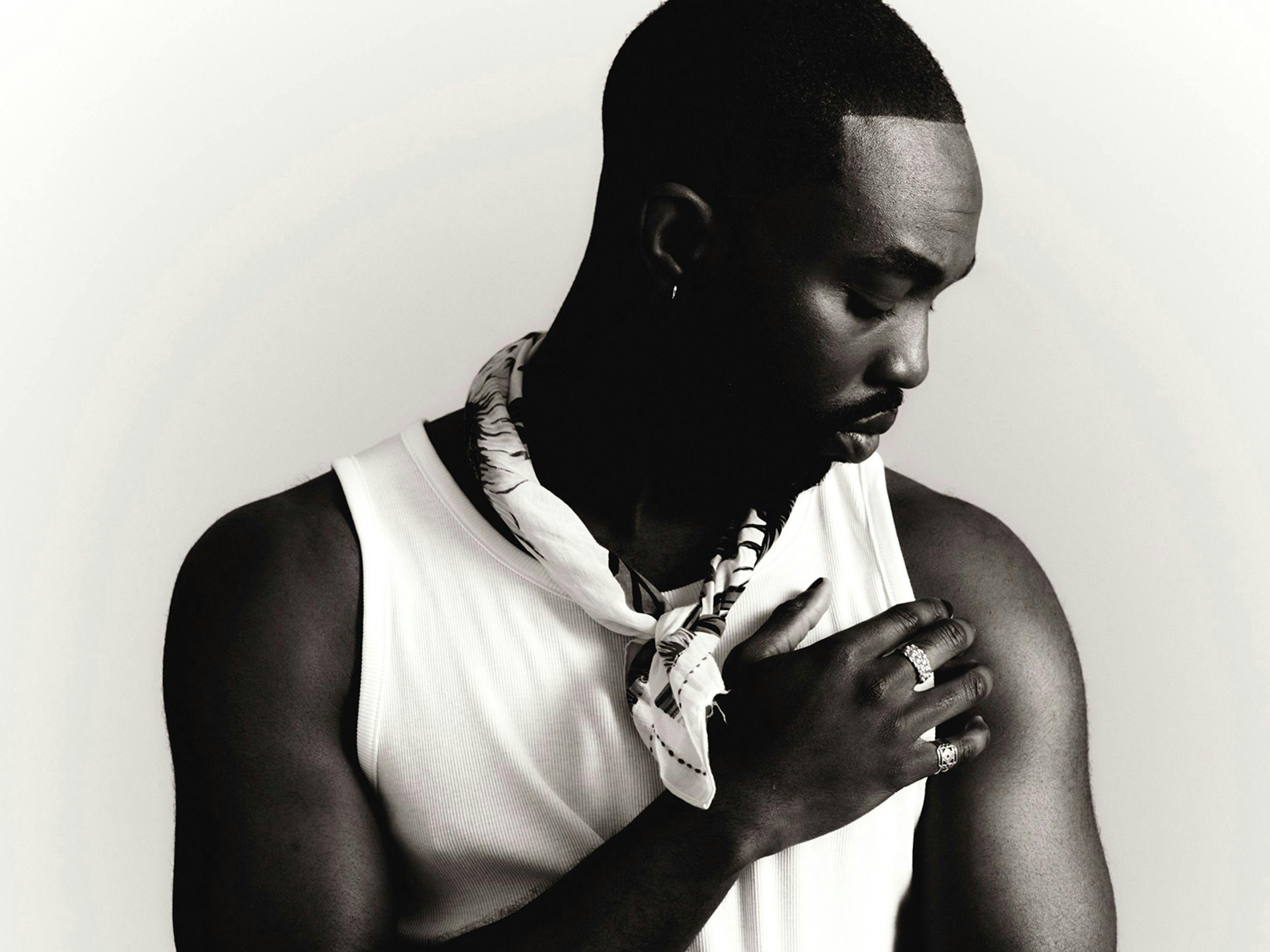

Brandon Taylor Turns His “Science Brain“ to Short Stories

It’s been five years since Brandon Taylor left his life as a doctoral student in biochemistry to become a writer, and he’s still getting used to it. Though his short story collection Filthy Animals, the electrifying follow-up to his Booker Prize-shortlisted début Real Life, was recently released by Riverhead Books, and his nonfiction essays are widely acclaimed, he nevertheless has a hard time believing that writing is now his job. “I used to think that when one was a full-time writer, one’s life looked like Stephen King’s or Danielle Steel’s or Nora Roberts’s,“ he says. “When I look at me and my Iowa City apartment,“ he says, “with books and books and books everywhere, and I can barely even remember to pay my light bill on time, I’m like, ’Is this the life of a full-time writer?’“

Many of the stories comprising Filthy Animals, which, like Real Life, takes place in a college town, deal with the bewildering, often painful experience of adjusting to change. Several of the characters, all of whom feel too broken to be accepted into polite society—“feral,“ as Taylor puts it—each struggle to navigate their uncertain futures: A moderately gifted dancer comes to terms with a career-threatening injury. A young woman who has only known hetero-sexual relationships falls in love with another woman for the first time. Lionel, a graduate student studying pure math, is forced to take medical leave and finds himself adrift in the vastness of life outside academia.

That feeling is not unfamiliar to Taylor, who loved writing since childhood but only left science to pursue it after he was accepted into the esteemed Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2016. “When I was training as a scientist, I had a sense of what my next career trajectory would look like,“ says the author, who grew up outside Montgomery, Alabama, and dreamed of becoming a neurosurgeon. PhD, post-doc, faculty job, researcher: The linearity of the academic life can be comforting, especially in retrospect (I can attest, as a former biology graduate student myself). “Now that I’m a full-time writer, I’m writing, but it doesn’t feel like I have a profession,“ he says. “I feel like I have a vocation and a calling as an artist, but I don’t yet know what the professional side to that looks like.“

Life is never as orderly as science may suggest, and Taylor, though he may not have realized it yet, has built a brilliant career on his impressive talent for capturing—and celebrating—the mess. In a tense narrative that runs through several stories in the book, Lionel becomes entangled in a sexual relationship with a manipulative heterosexual couple, who toy with him like cats with a mouse. The jarringly visceral title story, which Taylor calls the “geographical center of the book“ and wrote over two hours in 2016, revolves around a young man who is in love with his swaggering best friend but is afraid to admit it.

Drafts of the stories in Filthy Animals were completed by 2016—before Real Life, which was written in April 2017—but have morphed alongside Taylor as he grew as a writer, becoming “more and more able to make the tough choices I needed to make as an artist.“ The result: A collection of stories that fearlessly lay bare the violence of human relationships while revealing the tenderness enmeshed in the brutality.

One way Taylor does this is through his ability to find the emotional heart of the small, seemingly insignificant moments that make up a life: Anxious at a party, Lionel hides in the bathroom and runs the faucet, so the person outside thinks he’s finishing up. A woman named Marta is irritated when her partner smiles at her during a gathering at a bar, “as if she were checking on a pet.“ Grace, a young woman with an inoperable tumor, notices the warmth of the vegetables her grandfather just dug up from the garden.

Sometimes, the granularity of these descriptions calls to mind an anthropologist in the field or a researcher at a microscope, taking notes from a distance. Lionel, watching guests at a party, notices that they “looped arms and hooked thumbs into each other’s pockets,“ “spooned things onto each other’s plates,“ and whacked ice cube trays—empirical evidence that humans crave touch, and fall comfortably into roles. “I still process the world in the same way,“ Taylor says. “You never get out of ’science brain.’“

These days, he says, his writing is less “driven by a representative impulse“ compared to his impetus for writing Real Life, which put a Black, queer scientist at the heart of a campus novel, a traditionally white-centric genre that Taylor loves but has glaring shortcomings in terms of race and gender—much like the ivory towers of science themselves. Many campus novels that do include Black people, he says, are “so concerned with whiteness that it was so tedious to read.“ His focus seems to have shifted, but only slightly: In Filthy Animals, the first character introduced is a Black, queer academic (Lionel), and many of the other stories center on queer relationships, but there are more working-class characters adjacent to the academic world who “are having to contend with the tedious gestures and postures that liberal people in the humanities tend to affect,“ he says. As a scholar named Sigrid rails about the ills of capitalism in the unexpectedly gentle story “Anne of Cleves,“ for example, her partner, who works in a plant, thinks: “Someone’s got to pay for all that living.“

To read Filthy Animals is to get a crash course in compassion: Realizing that everyone may feel as broken and confused as you makes it a lot harder to pass judgment on others and oneself, and perhaps a little easier to keep moving forward. Lionel finds respite from his constant bewilderment in the short story “Meat,“ when a lover’s intentions become obvious as he tugs on Lionel’s pubic hairs: “It was a comfort to him, this math. This easy, direct calculus. All of life was shifting equations.“

Maybe most of those equations are unanswerable. But as Taylor continues to show, there’s great beauty—and pain—in the attempt to solve them. “It’s really hard to understand what motivates people or how relationships between people work,“ he says, but there is “lucidity that comes from moments of clarity: the clarity of pain, or the clarity of human motivation.“

“It’s a nice respite from the whirling mass of confusion that is typically human relationships for Lionel—and also me,“ Taylor laughs. “It’s like everybody’s reading from a script that I just did not get that day.“

Filthy Animals is out now. Read this story and many more in print by ordering our Summer 2021 issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.