Vintage shirt by Armani Collezioni. Vintage tights.

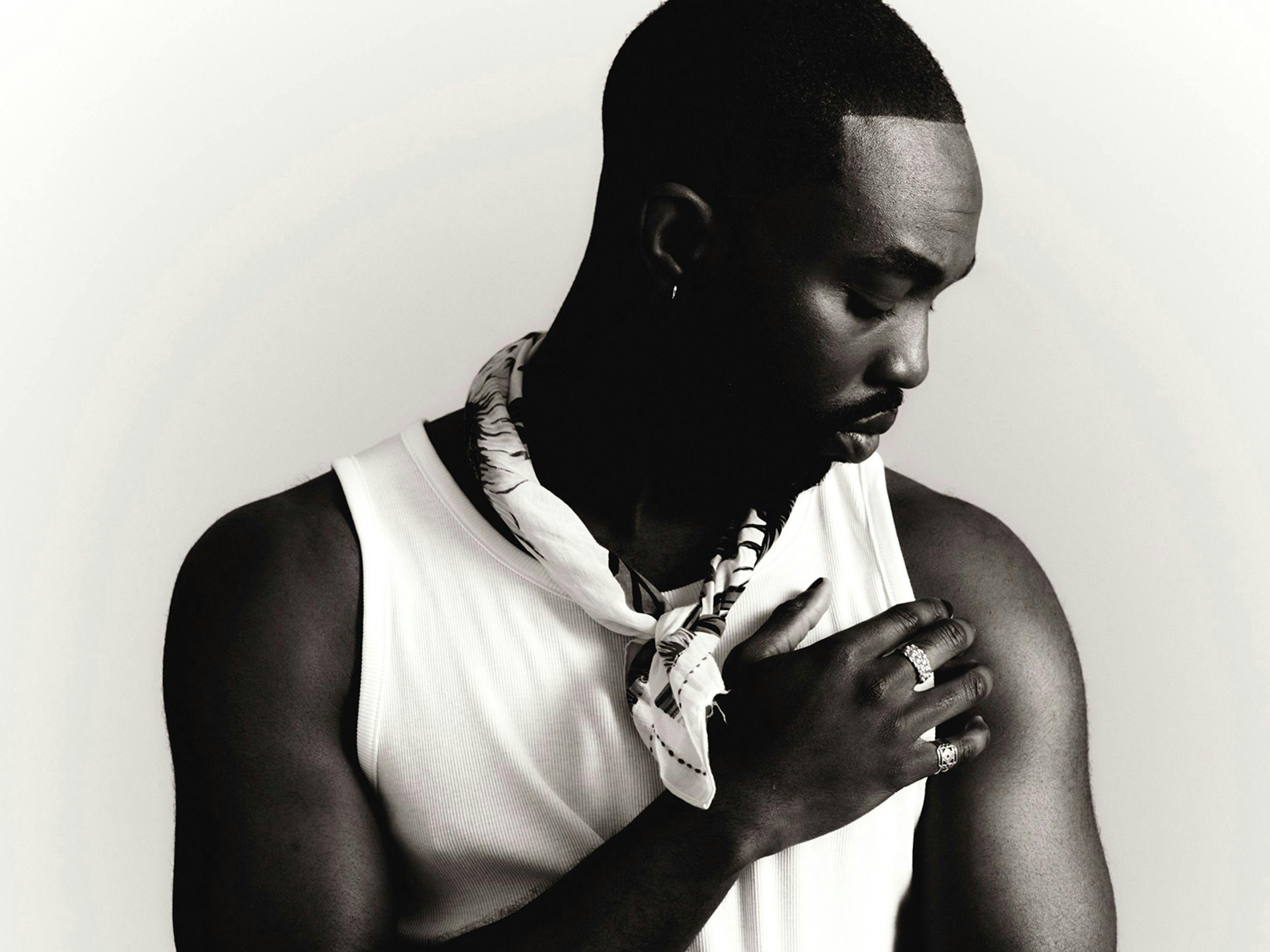

Live from New York: Calvin Royal III

Last spring, everything was lining up for Calvin Royal III, then a soloist at American Ballet Theatre. He had been cast in the company’s spring season at the Metropolitan Opera House in some major roles—as Albrecht in Giselle and as Romeo in Romeo and Juliet, which he was slated to perform alongside Misty Copeland, the first time in ABT’s eighty-one-year history to feature Black dancers in both title roles. Ballet, an artform that began in the courts of Europe and maintains its lily-white reputation to this day, has whiteness encoded in its very æsthetics, and there are still major companies in the United States that have never promoted a Black dancer to the rank of principal. The schedule would have allowed Royal to show he was up to the task of performing leading roles in ABT’s repertoire before being promoted to the highest level. “I was a soloist stepping into these principal roles,“ he recalls, “and for soloists to do that, there’s a lot of expectation—proving to myself, but also to the public, that I paid my dues and deserve to be doing those title roles.“

In March 2020, he was on ABT’s California tour, during which he was scheduled to premiere in Alexei Ratmansky’s Of Love & Rage, a full-length ancient Greek epic based on Callirhoe, widely considered the world’s oldest novel. During the final dress rehearsal for the new ballet, Royal felt his body give out. “I went for the first jump in my solo and I slipped center stage and rolled over my ankle,“ he recalls. Then Covid-19 washed in like a tidal wave, and the world canceled its plans as ballet companies scrambled to figure out how to survive without live performance.

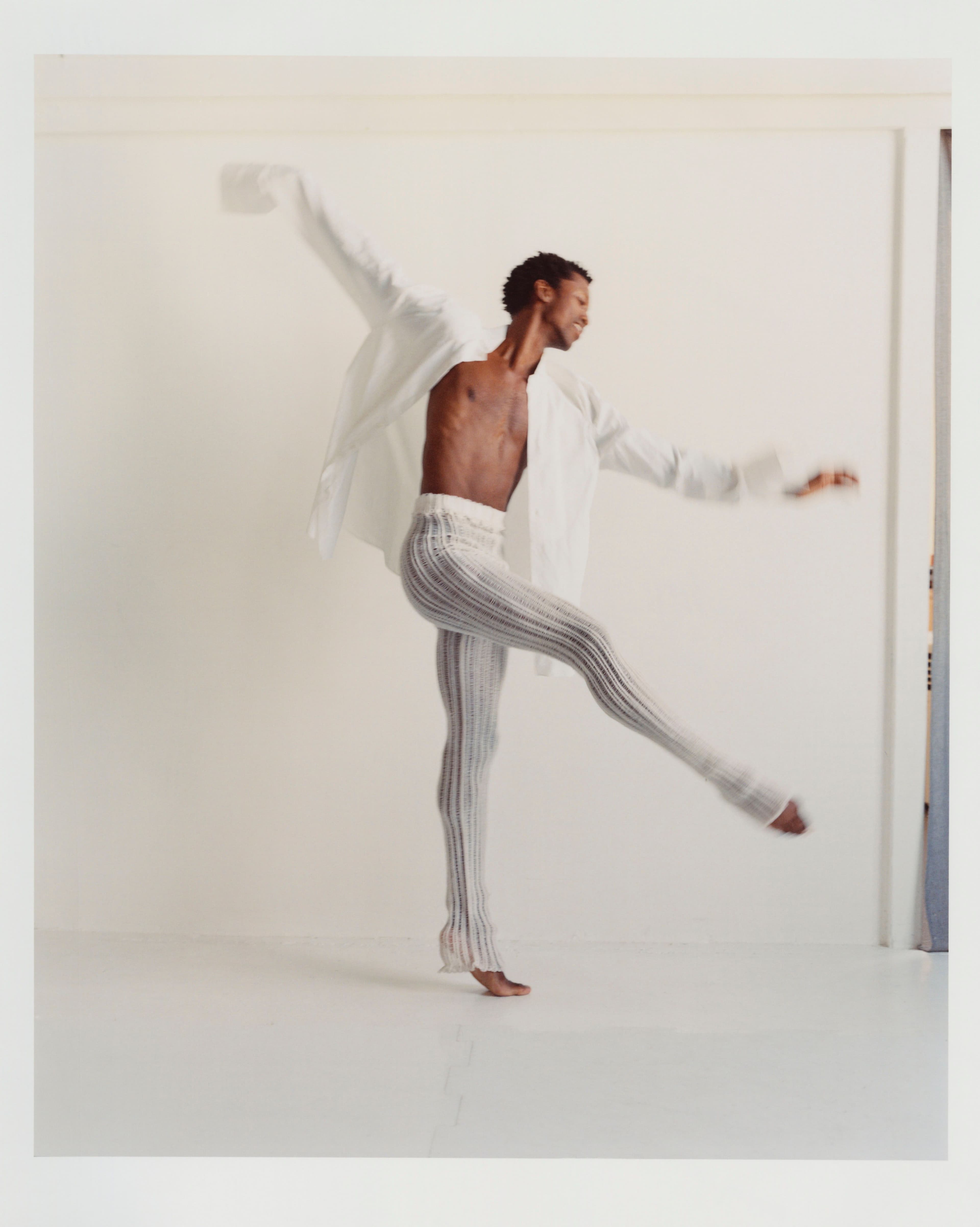

All clothing by Dion Lee. Vintage shoes by Giraudon.

Royal spent the first few months of the pandemic resting his ankle and FaceTiming with his physical therapist every day as he recovered. Stuck at home with unforeseen time off, Royal realized this time to stay off his feet was “a blessing in disguise.“

“In a way, the injury was my body telling me it was time to take care of itself,“ he says. Once he was back on his feet, he worked with one of his coaches on the roles he had been scheduled to perform before ABT shut down, taking advantage of the opportunity to revisit the works he had been cast in that had been canceled by the pandemic. He wanted to refine his technique but also work on the psychology of the characters he still aspired to dance. “I had that time to really focus on that,“ he says, “in a one-on-one setting where I could go for something and fall down on my ass and get back up and be okay, getting rid of the fear of really going for it again.“

Getting physically ready to dance principal roles is only half the battle though, and two months into the pandemic, after George Floyd was murdered by a police officer, Royal was forced to reflect on why dancing matters in the first place. “There I am trying to recover, trying to just put one foot in front of the other, and all of this stuff is happening around me,“ he recalls. “What does this mean? I remember asking myself, why is it that I do what I do?“

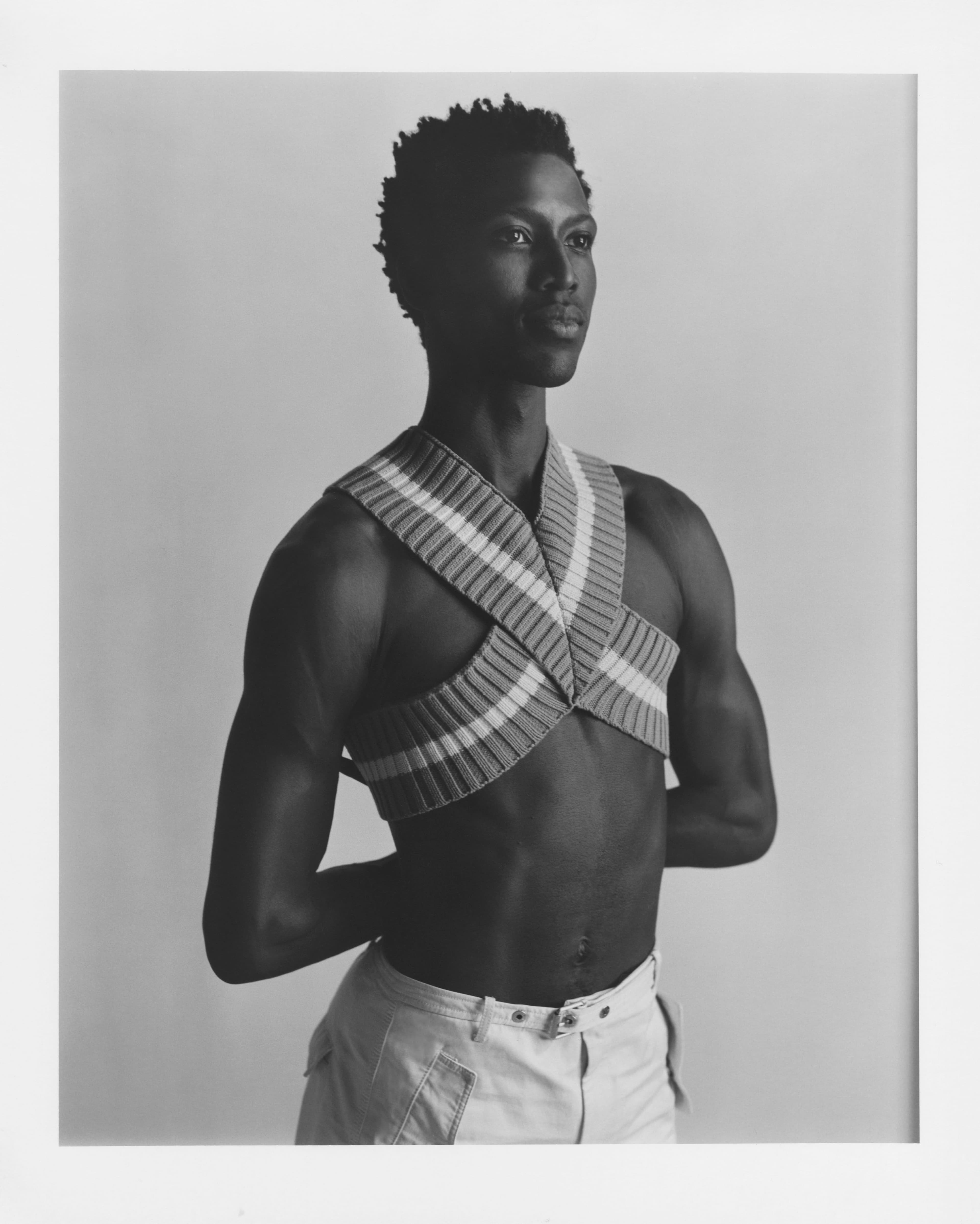

Royal devoted himself to figuring out how to make ballet better—more equitable, accessible, and just. The company “had lots and lots of conversations“ about ways to improve, and Royal brainstormed with other dancers to dig deep into their complicated feelings as Black performers. “What are the things that bother us?“ they wondered. “How can we enact change within our own sphere?“

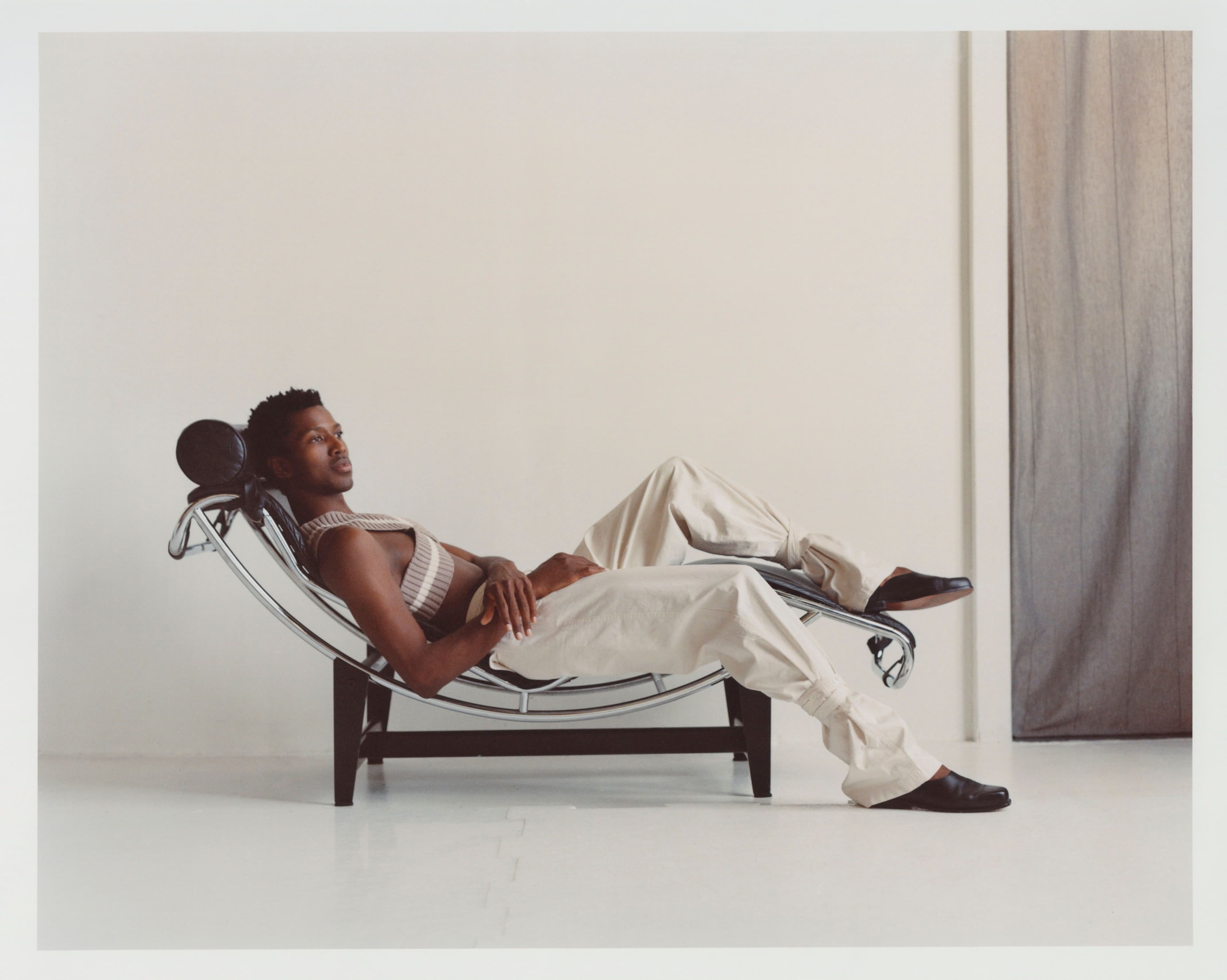

All clothing by Dion Lee

He thought back to the ballet he had been rehearsing when he sprained his ankle on ABT’s Los Angeles tour just before the company shuttered for the pandemic. One scene in particular had made him uncomfortable. “This heroic character who, at one point in his journey, gets everything stripped away from him and he’s taken into captivity, they referred to it as the slave scene,“ he explains. “He’s in shackles and he’s being whipped.“

Royal thought, “I’m going to eventually get on the Metropolitan Opera House stage and be whipped by my majority white colleagues, in shackles? I understand that it’s my character’s journey, however the implications outweighed the artistic choice to have the only black soloist dancer subjected to being whipped as a slave. That felt and still feels really wrong.“

At the time, Royal had brought up his discomfort with the choreography, but he felt the issue was not meaningfully addressed. It was only during ABT’s open forum after George Floyd’s murder when artistic director Kevin McKenzie was more receptive and “made a commitment that with my participation, he and Alexei Ratmansky“—the work’s choreographer and ABT’s artist-in-residence—“would rework the scene to get it right this time around,“ Royal says. The choreography will be updated for the company’s spring 2022 season.

All clothing by Dion Lee. Shoes, Royal’s own.

In September 2020, Royal was promoted to principal dancer—the second-ever Black man to hold this title in ABT’s long history. He says so much of inclusion and representation is unspoken: “We can talk but when you see it, that’s when people can see themselves and can feel like there’s a sense of belonging.“

“It’s an honor but also this huge responsibility in a way,“ he adds. “My hope is that [my] position will continue to generate more not just visibility and representation but [allow] more people to see themselves and chase their dreams too.“

Royal’s return to the stage this season has already seen him finally make his début as Albrecht in Giselle, and he will appear as well in “Touché,“ a new pas de deux by choreographer Christopher Rudd exploring male love—a groundbreaking moment for both Lincoln Center and ABT, and for Royal, who identifies as gay. He’ll also perform in “ZigZag,“ a new ballet celebrating the music of Tony Bennett. His goal for this season, he says, is simply to appreciate the present moment, from the opening overture to the final bow. “Being on stage, there’s something magical that happens. You live this journey that lasts for a few hours,“ he says, “and I just want to just savor the present moment because, like we all know, the present moment can be taken away in the snap of a finger.“

This includes appreciating the hard work of rehearsals. “The show is important, but the rehearsal process, of diving deeper into characters and trying different things and falling and getting back up—all of that to me is just so precious,“ he says. “I just want to savor it all.“

“Touché“ will have its live premiere tonight as part of American Ballet Theatre’s fall season. See the full portfolio celebrating the return of live performance to New York this season here. Read this story and many more in print by preordering our Fall issue here.

All clothing by Dion Lee

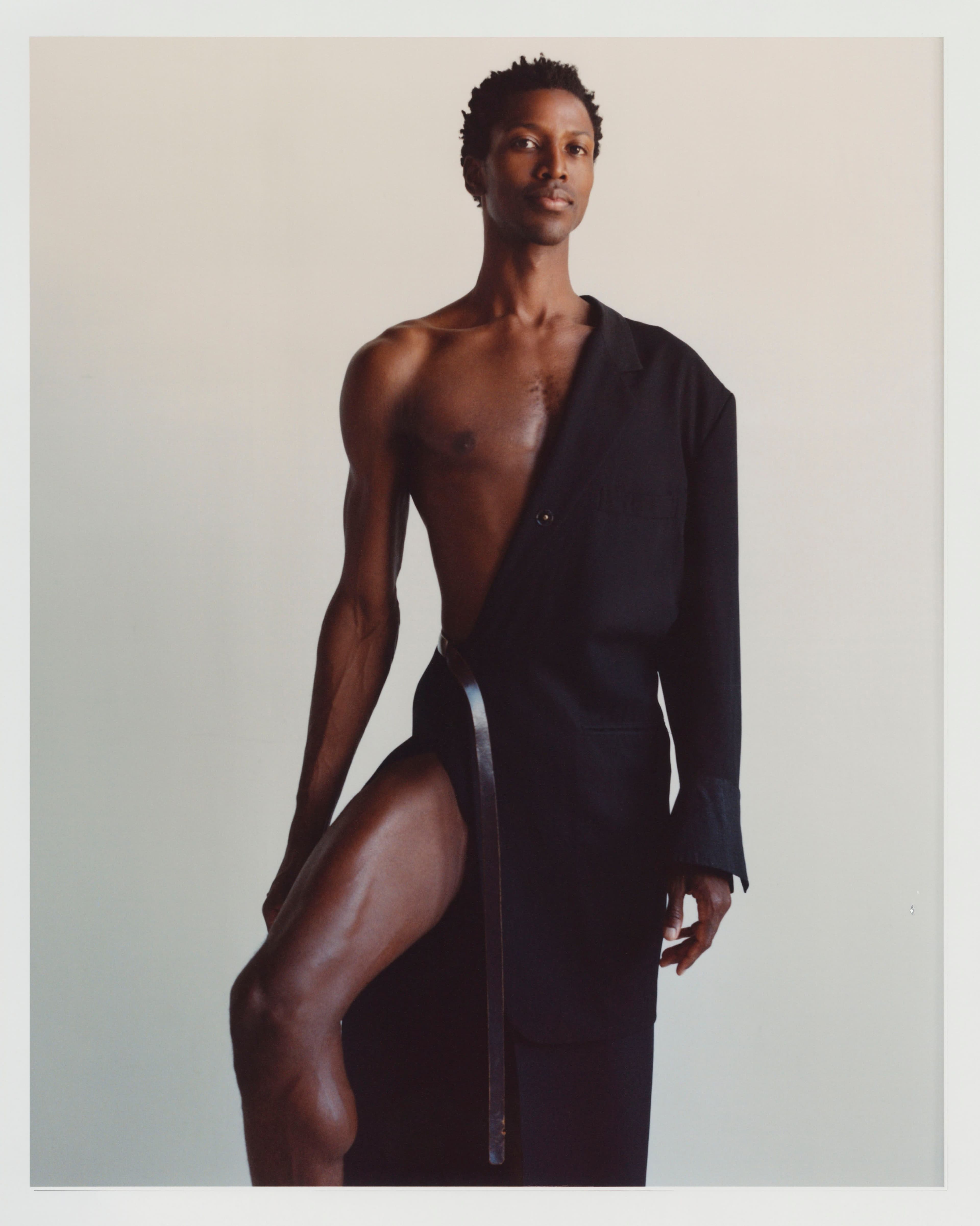

Vintage coat by Yohji Yamamoto. Skirt by Dion Lee.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.