TOP by Christian Wijnants. Vintage SKIRT by Jacquemus. BELT by Isshī. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin.

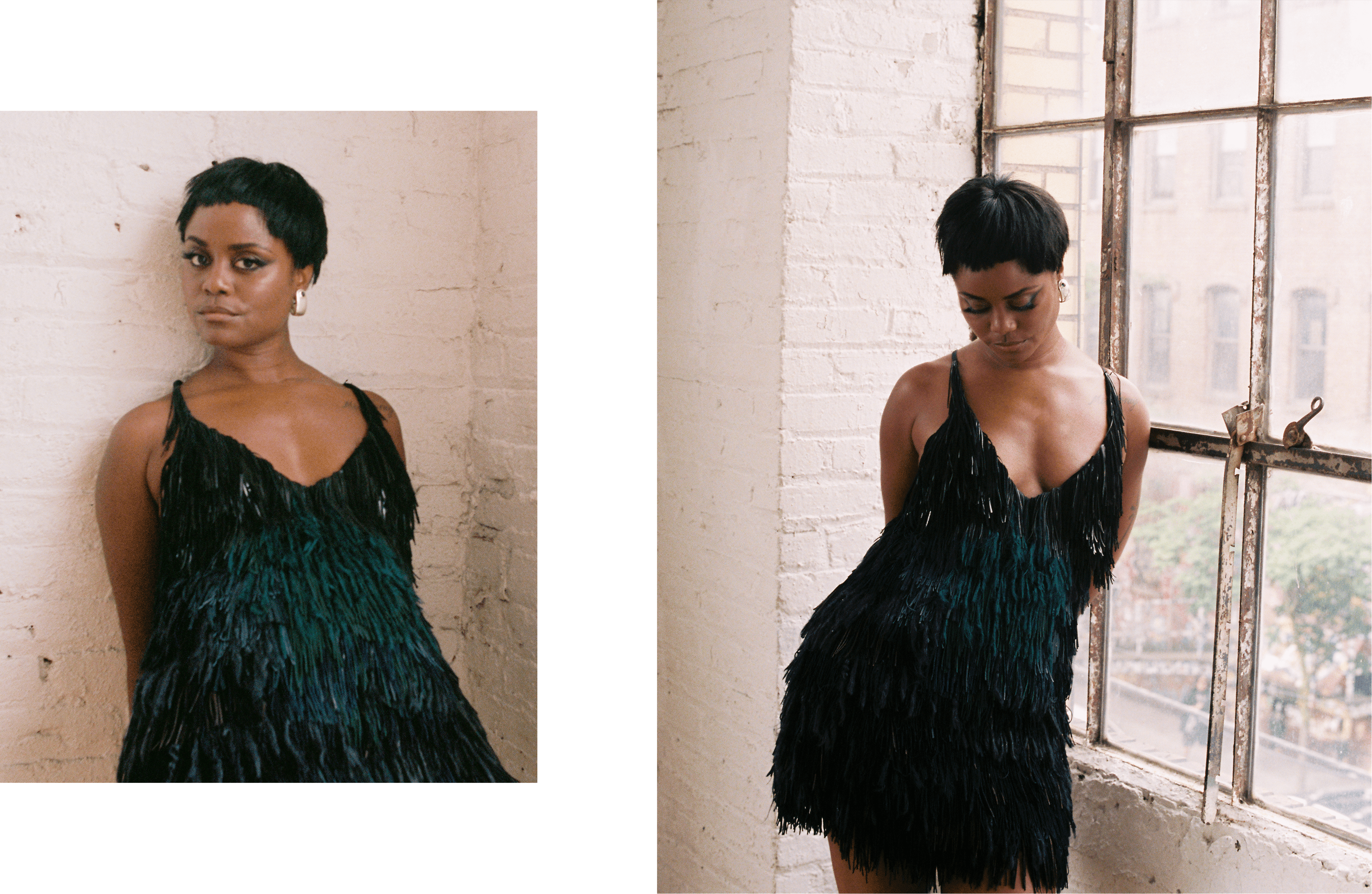

Denée Benton Is Expanding the Possibilities

There are artists who chase the current—and then there are those who subtly, steadily shape it. Denée Benton is one of the latter. Known to many as the clear-eyed, defiant Peggy Scott on HBO’s The Gilded Age, Benton is not merely acting within the frame—she is widening it. Across her career, whether onstage in Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 or Hamilton, onscreen in Julian Fellowes’s imagined nineteenth-century New York in The Gilded Age, or in her upcoming run in Pericles at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Benton works with a precision imbued with undeniable presence. Her ambition isn’t to lead a movement but to do the slow, deliberate work of widening the field—of roles, of institutions, of imagination. She treats her career less like a ladder to climb and more like soil to cultivate, making room for stories that might not otherwise take root.

In The Gilded Age, HBO’s critical smash-hit exploring the eponymous era of extreme wealth disparity and extractive opulence, Benton’s character has evolved into something rare to see: a Black woman moving through nineteenth-century society not simply as a companion or narrative tool, but as a fully imagined person shaped by her own community, grief, and desire. The work to reach that point was slow and collaborative. “[I gave] a lot of input on specific story and specific arcs and expansion,” she says. “But more than anything, it was really making sure that what we were trying to show onscreen was also supported offscreen.” That effort was consequential. As Benton tells it, what began with small adjustments—“What if Peggy says this instead?”—ultimately reshaped the show’s architecture: three Black women were brought on as co-executive producers and writers, and the presence of Black families like the Kirklands was no longer a gesture but a foundation. “What if we took up real real estate in this show?” she asks. “Now we’ve got the Russells, we’ve got the Van Rhijns—but we’ve also got the Kirklands, honey.” It wasn’t just a correction; it was an assertion of history. It expanded the world on screen and, more importantly, expanded who was allowed to belong within it.

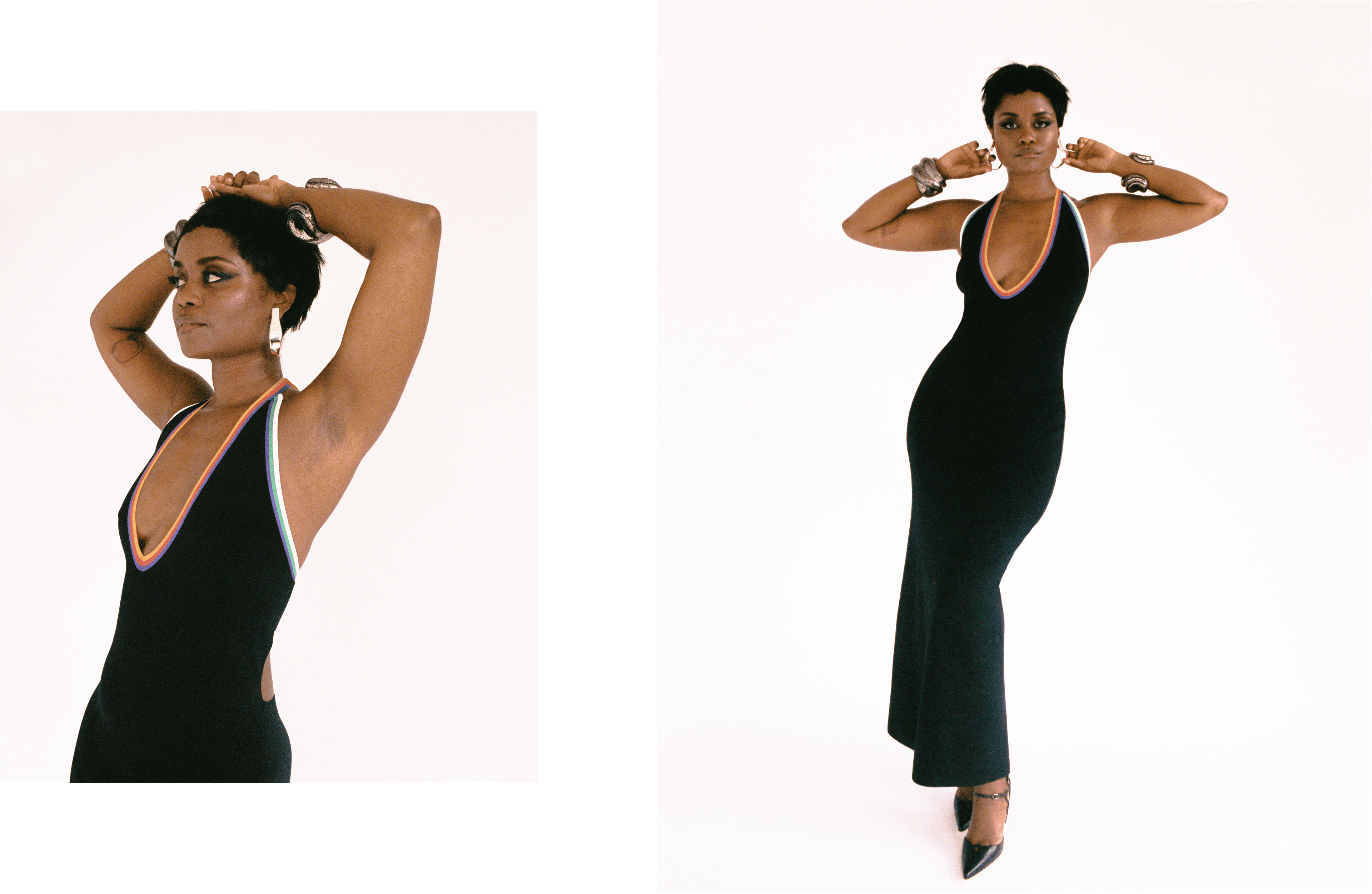

DRESS by Christopher John Rogers. SHOES by Manolo Blahnik. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin.

Rather than a performance of inclusivity, this is work in dramaturgy. It’s also the outgrowth of Benton’s own rigor—an actor who insists not just on roles but on voice. When asked what she brings to the table beyond performance, she emphasizes her ability to extend beyond merely delivering lines. “I really see myself as a co-creator,” she proclaims, noting that many directors she’s worked with have invited and encouraged her input. It’s something she’s honed in theatrical spaces—particularly her long-running collaboration with director Rachel Chavkin—and recently in film, with a Berlinale-premiered project alongside Shatara Michelle Ford that relied on improvisation in the style of Mike Leigh. “I’ve always been a deviser as well as an actor.” It is not uncommon for Benton to bring dramaturgical questions that lead writers and directors to rethink tone, stakes, or structure. Her ability to shape story through lived inquiry, not just dialogue, is part of what allows her characters to feel inhabited rather than interpreted.

If there’s a throughline in her work, it’s not so much thematic as energetic. “I really play a lot of women who, in their core, are trying to get free,” she says. That arc—liberation through resistance—resonates personally. Benton, who was raised Pentecostal and came out as queer later in life, describes her own experience of breaking molds as deeply spiritual. “There is something also that feels spiritual about that to me because there’s a liberation exchange. You’re putting that kind of energy into the world.” These characters aren’t simply written to be strong or resilient; they are excavated through Benton’s empathy and will. She gives them breath not just through line reading but through interior alignment. Rather than portraying freedom as an endpoint, Benton allows her characters to inhabit its messy, tender pursuit. Her performances don’t resolve so much as reveal the layers within that process.

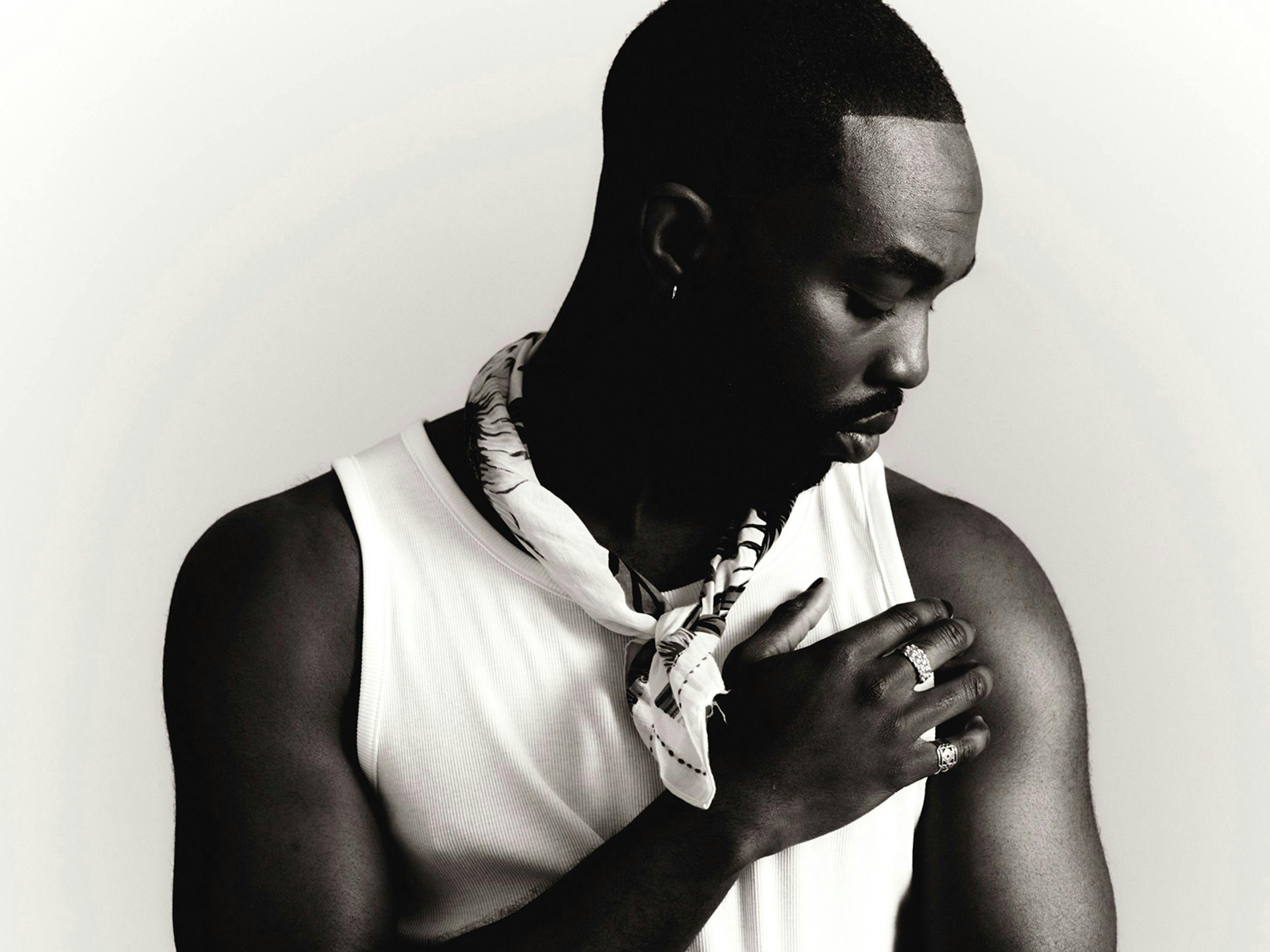

JACKET by Stella McCartney. All JEWELRY by Isshī.

She’s alert to the broader ecosystem that artists are navigating—or barely surviving within. “None of us can ignore the fact we’re living through another Gilded Age,” she states frankly. “You have these extreme Jeff Bezos weddings, while Venus Williams is going back to play tennis because she didn’t have healthcare. The disparity is insane. How many artists would be working enough to live a sustainable life in New York ten years ago? Now it’s pretty untenable.” Yet Benton doesn’t just criticize—she returns again and again to examples of what is working. She cites Public Works, the participatory theater program run by the Public Theater in New York, where Broadway actors perform alongside community members in reimagined classics, as “a real answer to places like PBS and NPR losing funding.”

She applies that same lens to her own sense of responsibility, particularly in moments of political crisis. When she speaks about the genocide in Gaza or the punishing retaliation artists have faced for speaking out, she is thoughtful but unafraid. “I don’t know why some people got dropped from their agencies by speaking out and why some people didn’t,” she says. “I don’t understand the tightrope.” There’s no illusion of safety in silence, only a question of how to act in ethical alignment. She often returns to examples like Aretha Franklin, who famously posted bail for Angela Davis without fanfare or fear. “People use the resources they have in different ways,” Benton says. “We all have a proximity to power that we can dance with.”

LEFT: TOP by Christian Wijnants. Vintage SKIRT by Jacquemus. BELT by Isshī. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin. RIGHT: DRESS by David Koma. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin.

Her own compass is built, in part, from the examples of activists and organizations she admires—the first to come to mind being Raquel Willis’s work with the Gender Liberation Movement; Prentis Hemphill for her healing, somatic work; and Make the Road NY for helping people “survive the ICE Gestapo we’re living through this moment.” Benton is quick to admit that she doesn’t always know how to walk the line herself. “I ask a lot of advice from people like Cynthia Nixon,” she says. “She’s able to move publicly and still hold on to their integrity.” Two years ago, Benton did exactly that. During the live 2023 Tony’s broadcast, she drew a similarity between Governor Ron DeSantis and the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan to immense pleasure from the crowd—her statement swept across the cultural press the next morning and made national news.

When asked what kind of legacy she hopes to leave, she doesn’t mention awards or platforms. “‘That was a great craftswoman,’” she explains of how she would like to be remembered. “‘Someone who really understood how to bring herself to a character. Someone who widened the lens on reality.’” It’s a response so spare and unassuming that you might miss its quiet defiance. She is not trying to be everything. She is trying to be real. And still, she dreams forward. She wants to play Lady Macbeth. “I’ve played a lot of pure-hearted souls,” she says with a smile. “It would be really fun to play against type and play some twisted, evil people as well.” She imagines herself in genre roles, even science fiction—“a dictator alien in space,” she suggests, full of curiosity. These aren’t deviations from her previous work. They are continuations of it, filtered through new forms. They allow her to imagine freedom beyond historical trauma, beyond domestic period drama, beyond the burden of uplift.

LEFT: TOP by Christian Wijnants. Vintage SKIRT by Jacquemus. BELT by Isshī. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin.

To do that, Benton is beginning to build the scaffolding for what comes next. Like many actors of her generation, she’s interested in producing, in originating roles rather than simply auditioning for them. She points to Tessa Thompson as a model: someone who’s moved behind the camera, built production companies, and created worlds where she can work on her own terms. Benton’s not there yet, but she’s thinking about it.

The tools she’s gathered in black boxes and green rooms—the improvisational muscles, the dramaturgical ear—will serve her well. “When I first got into the business, people had such limited imaginations around what Black women can do that it’s always been a part of me to be like, ‘No, I want to expand this imagination with you,’” she expresses. “I didn’t realize I was developing a skill while I was doing that. I’m excited to see the way it can show up over the next decade as I gain more leverage and visibility.”

The Gilded Age continues on Sundays on HBO.

DRESS by Gabriela Hearst. All JEWELRY by Patricia Von Musulin.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.