Doug Aitken, New Ocean, 2001 (still), from Works 1992-2022 (MACK, 2022). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Doug Aitken’s Works

Over the course of three decades, Doug Aitken has established himself as an inimitable and omnivorous voice in the art world, with creations in photography, installations, architecture, and video. A comprehensive new book, Works 1992-2022, offers a career-spanning look at his artistic process, alongside a range of essays and interviews, including one from 2021 with Max Hollein, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, exclusively excerpted below. In conversation about his recent work Flags and Debris, Aitken demonstrates the drive of a restless imagination that finds a way to create under any circumstances.

Doug Aitken, ’Flags and Debris,’ 2021 (still), from ’Works 1992-2022’ (MACK, 2022). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Flag and Debris was a very organic process for me. In March 2020, I recall distinctly, I was in Europe and started receiving phone calls saying, “You have to come back immediately, borders are closing, nobody knows what direction things are going to take.“ March and April were a very difficult period for everybody. I started to see the world around us closing, the door shutting and locking. I started to think about the idea of making art. I asked myself what materials were immediately around me. I borrowed from the Arte Povera approach. I looked around my house, and found things in the garage—old clothes, discarded and castoff materials—and started cutting them up and sewing them into words, phrases, and sentences. As I was doing this, the language that I was using shifted towards phrases and language that was more future-forward: data mining, digital detox—language that mapped a world that was unfolding in front of us. I used these basic tools and time-consuming techniques like sewing, because it allowed me to slow down these ideas. It becomes almost meditative when you’re working on something which is so purely physical or manual.

This was the first part of the project, and that grew into a larger body where the flags or banners were also like protective covers or blankets you could wrap yourself in. At one point, I had a piece that was almost finished and I slid it over my body and wrapped myself in it. This made me ask what would happen if bodies were inside these works—if we took this simple project centering around language, text, and shelter, and activated it somehow. I reached out to a dance group that I liked, the Los Angeles Dance Project. They were interested and it led to a choreography that I created. We rehearsed in a parking lot in downtown Los Angeles every day. We couldn’t use indoor studios. The dancers would try different body movements while wrapped in material. Every day we’d reduce it more until we had this minimal set of movements. I had the idea to take it out into the city and film, because the city was largely empty due to Covid, with little traffic, police, or security. We could stage impromptu scenes and perform in offsite locations, then use film to distill moments and sequence them into a narrative. It was conceptual in a sense, but also intuitive. One thing led organically to another.

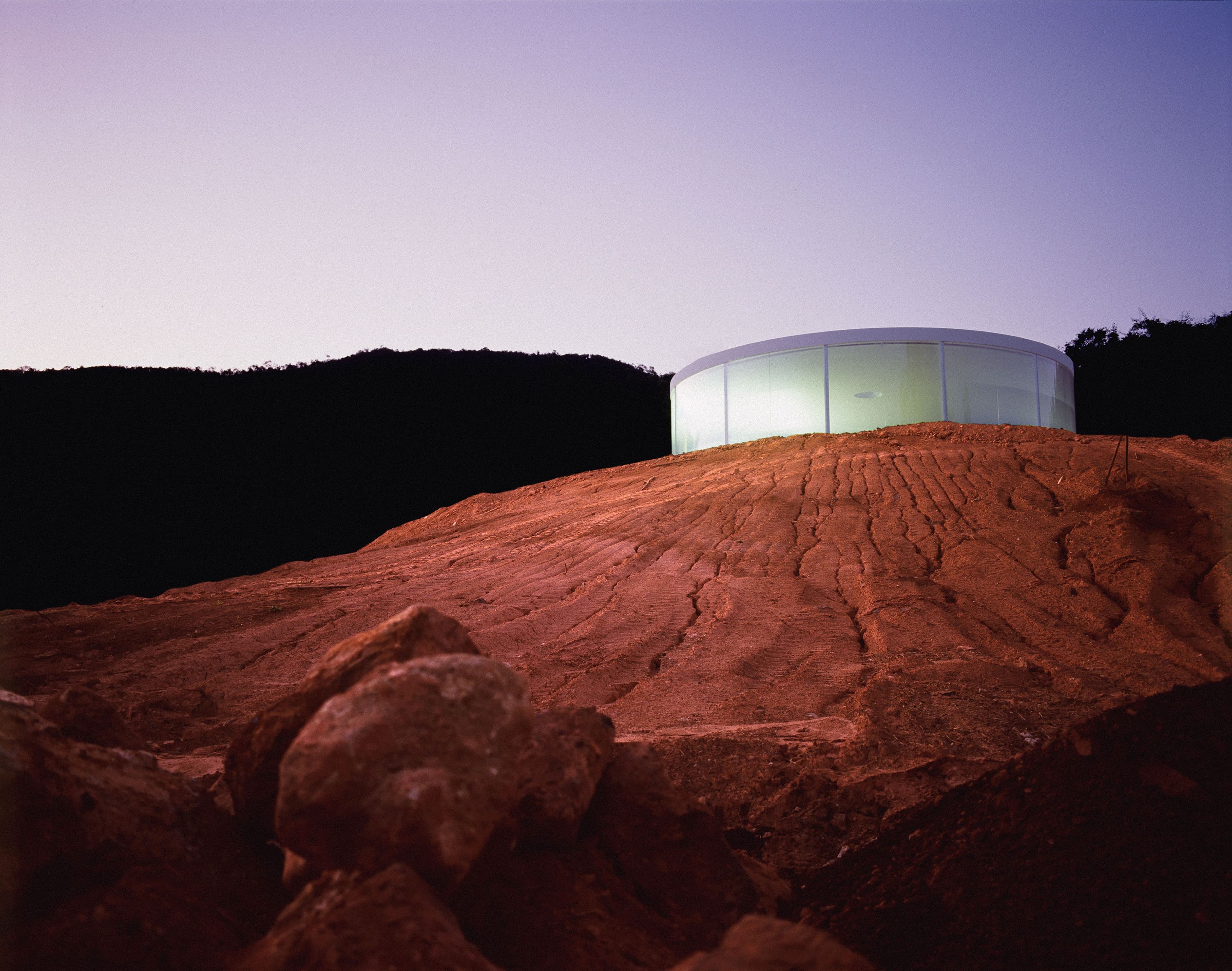

Doug Aitken, ’Sonic Pavilion,’ 2009, from ’Works 1992-2022’ (MACK, 2022). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

When we were filming this project, I would drive around every night alone through desolate industrial areas, looking for an area where there was some light coming off a factory that could illuminate a parking lot. Or a street corner that had a certain quality to it. A few weeks later, I would come back with a dancer and say, “Okay, we’re going to climb this fence, or go to this river basin, and film here and now.“ It was rogue in the sense that we could move as if the city was asleep and you could do anything and go anywhere to make what you had to. With Flags and Debris, there were no permissions to seek and no one to ask.

It made me start focusing on the earth. During the pandemic, I started developing new projects and proposals, writing texts, making images, even animations for new ideas. Doing this allowed me to breathe and explore other possibilities. These projects really developed out of the realization that we could not be reliant on traditional art structures.

So that’s something that is fascinating me right now. Where can art go? How can it communicate in different ways and change continuously? Could you have a dialogue with an artwork that is evergreen?

Works 1992-2022 is out now from MACK. Read this story and many more in print by ordering our fifth issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

Doug Aitken, ’migration (empire),’ 2008 (still), from ’Works 1992-2022’ (MACK, 2022). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.