DRESS by Dior. RING by Erede.

Gayle Rankin Wants to Know More

“I don’t think I’m that interesting,” says Gayle Rankin, the Scottish actor currently playing Sally Bowles, the “Toast of Mayfair,” in Broadway’s latest revival of Cabaret. She is perched in her dressing room, adorned in green-gold macramé, her short bleached-blonde hair pinned off her face and blue eyes shining underneath. “I think other people are more interesting than I am and I’ll be along for the ride.” Rankin is coming off another interview before preparing for the night’s performance of Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club. The New York transfer of Rebecca Frecknall’s 2021 West End production of the nearly-seventy-year-old musical by John Kander, Fred Ebb, and Joe Masteroff is hosted at the historic August Wilson Theatre, which underwent a full gutting and subsequent restoration for the immersive rendition. The new stage is set on a circular platform through which Eddie Redmayne’s Emcee emerges; the audience members, seated in concentric rings, see almost as much of each other as they do the actors. The production has since received nine Tony Award nominations, including Best Revival of a Musical and Rankin’s for Best Actress in a Musical.

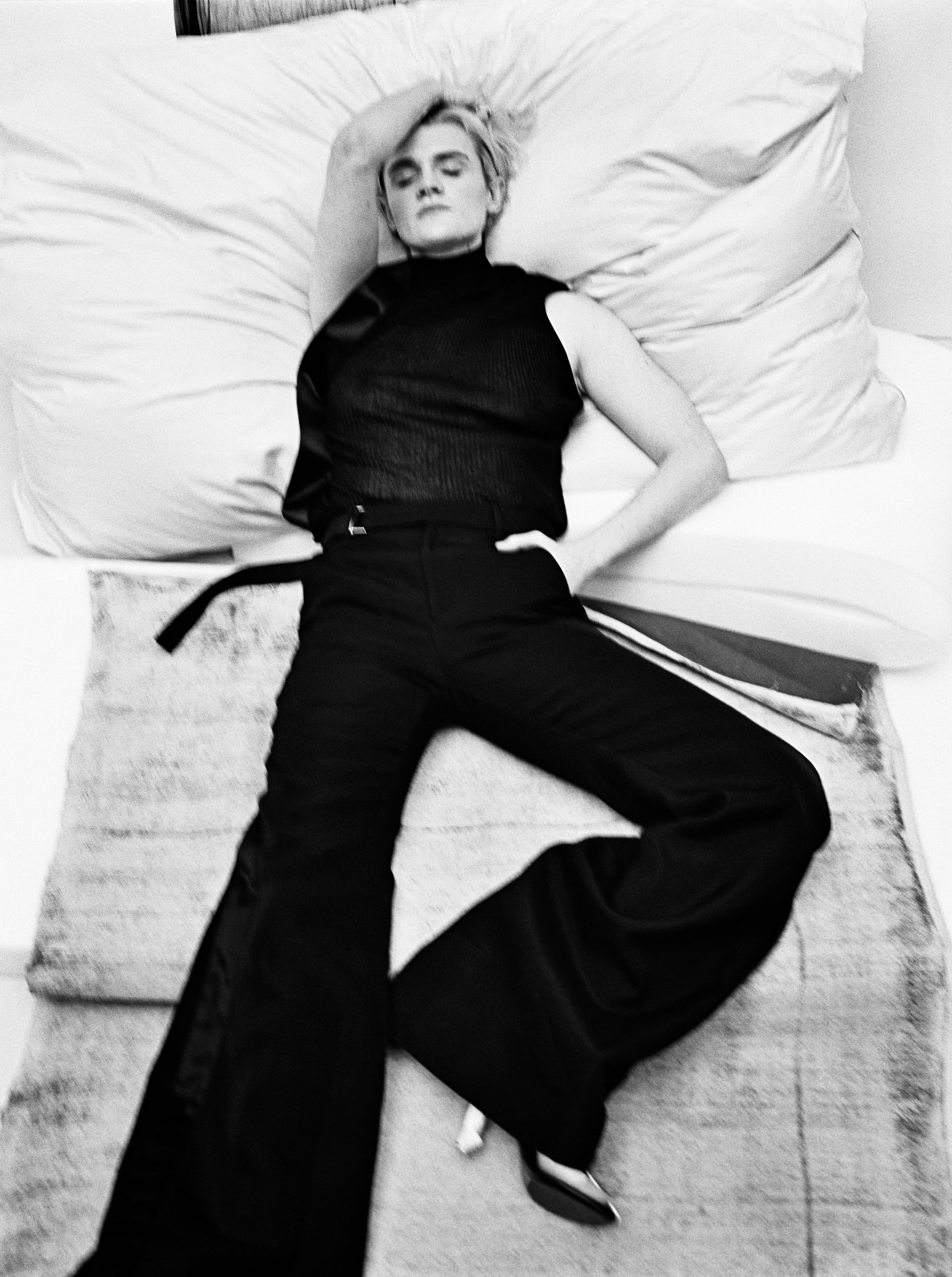

All CLOTHING by Ashlyn. SHOES by Stella McCartney.

Here, a few hours before she’s back on stage for the fifth—of eight—performances in a week, Rankin reflects on her own innate curiosity about others and how it has shaped her portrayal of the varied characters she has played throughout her career, from the species-dysmorphic professional wrestler Sheila the She-Wolf on the Netflix series GLOW to Sally Bowles. Before The Kit Kat Club, Rankin played the prostitute Fraulein Kost in the 2014 Roundabout Theatre Company revival of Cabaret alongside Michelle Williams and Alan Cumming. Her wide-ranging interests can be seen in the breadth of her previous roles, including a college student in love in 2015’s comedic play The Mystery of Love and Sex at Lincoln Center, Ophelia opposite Oscar Isaac in Hamlet in 2017, and a punk rocker Alex Ross Perry’s 2018 film Her Smell. As a child in rural Scotland, Rankin spent most of her time alone in nature with her imagination or quietly observing others. “I’ve always been really curious about people—completely dumbfounded by and curious about people,” she says. This quality, along with her lifelong love of music, led to a sense of always being compelled toward the stage (she wanted to be an opera singer first) and she began training with a singing teacher at the age of eight. “Things just kind of tumbled from there,” Rankin recalls. “I would keep asking my parents, ‘I think I want to do this, I want to do this, I want to do this.’ It just kept unfolding.”

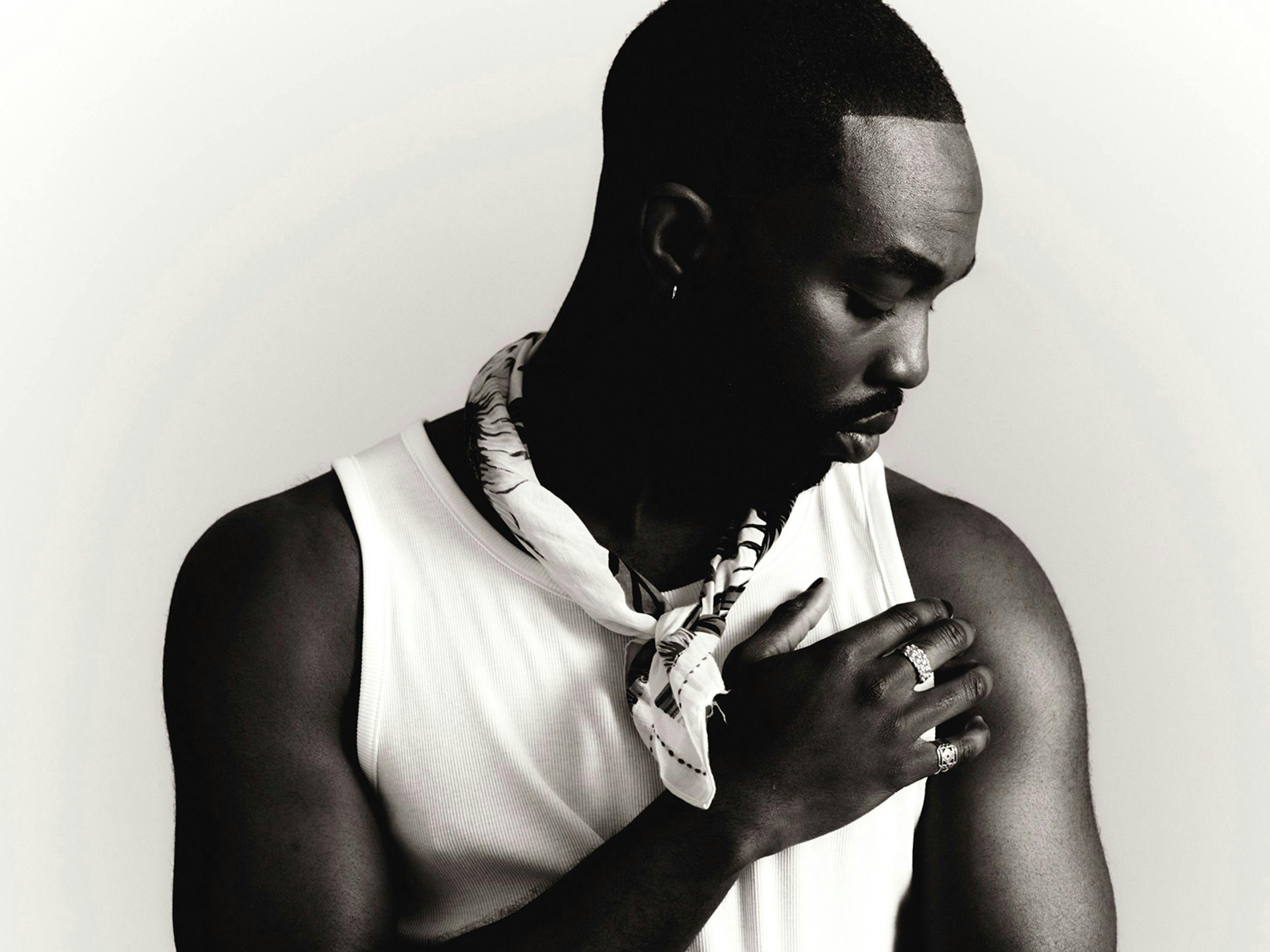

TOP by 3.1 Phillip Lim

Sally Bowles, the heroine of Cabaret’s imperfect and flawed (“deeply flawed,” Rankin emphasizes) cast of misfits, creatives, and club-goers who make their home at the fictional Berlin-based Kit Kat Club against the backdrop of a rising Nazi Germany, has been a theatrical icon since she was first played by the actress Julie Harris in John Van Druten’s 1951 play I Am A Camera, later revived by Jill Haworth on Broadway in the original production of Cabaret in 1966 and portrayed by Liza Minelli in the 1972 film. She was first brought to life in Frecknall’s London production by the Irish actress Jessie Buckley, who also starred alongside Redmayne’s Emcee, the play’s deeply unsettling, clown-like, seductive and simultaneously nightmarish narrator. Rankin, whose Sally feels particularly current—a contemporary woman with a creative mind—says she thinks the character is often misunderstood by audiences. “I see [Sally] as a phoenix that rises from the ashes in a kind of breakthrough, rather than a breakdown,” the actor says. “I’ve always been really fervently attached to at least trying to understand it for myself so that I can portray her in a way that I want to portray her while staying true to the text.” As a rule in her work, Rankin aims to give something, tangible or not, to the audiences to which she performs. With complex and hard-to-pin-down characters like Sally, all she asks is that viewers remain receptive. “Sally is so prophetic and smart and kind and generous and present,” gushes Rankin. “She has pretty big secrets about the world and being a woman in this world, about being a creative woman in this world, about being a human being.”

DRESS by Ashlyn. SHOES by Louis Vuitton.

In spite of her talents, what makes Rankin fascinating is her ability to strike a fine balance between humility and confidence. She seems genuinely interested in the pursuit of understanding each of her characters and is apparently unafraid of putting herself out there to make sure they are seen and heard by the world. In performances and interviews, there is a sense of fierce defensiveness and protectiveness for the characters she portrays. It is important to her that audiences open their minds—and listen. She says that in a musical like Cabaret, with its sensitive, occasionally divisive subject matter, closed-mindedness has no place. “The only way progress is going to happen is if people open their minds,” she adds, by which she seems to mean an openness itself to the imperfect nature of others, rather than a singular definition of morality. Her lifelong interest in the mystery of human individuality serves her well in Cabaret, which offers much to explore throughout what starts as a glamorous, flashy display of debauchery and hedonism and quickly descends into the harshest reality. “There is a huge question inside of the musical,” says Rankin. “One of the most amazing songs is Bebe Neuwirth’s song ‘What Would You Do?’ It is the question we’re all asking. There’s nothing didactic about it.” If there is an answer, right or wrong, no one offers it.

DRESS by Tory Burch

Again, this is where Rankin appears most comfortable: protecting and defending the characters she brings to life. If not in a motherly way, then as their champion. That is not to say she is defensive about her own performances; rather, she is staunch in her protectiveness over the characters themselves—determined that they are understood, that they are heard with compassion and empathy. Almost as if they are real. It is this trait (in addition to her raw musical talent) that threatens to make her very successful. Of her upcoming role in House of the Dragon’s second season, she describes “without giving away too much,” Alys Rivers as someone who brings “a whole different aspect to the show, a really new element. She has a lot of power and a lot of mystery and is very cool.” Rankin says she fell in love with the show and is thrilled to be part of it.

DRESS by Gucci. RING by Erede.

Though seemingly self-assured, Rankin is certainly more comfortable in the role of uplifting others—even fictional others—than herself. “Oh god,” she says as she confesses that Real Housewives is her favorite thing to watch on television. “It’s so exposing.” Offstage, her favorite things are the “basics”: “I love being in nature. I love traveling. I love going to museums, I love art.” When she has the time and space, she particularly likes to cook. “It is so different from acting, which you’ll never get right,” she explains. “But you can make a cake and it can be good. Like a really good carrot cake. Or a pavlova. Or a roast chicken. Really fucking good.”

All CLOTHING by Sacai. SHOES by Louis Vuitton.

As soon as her current stint as Sally Bowles wraps, Rankin will be quickly in the pursuit of whatever comes next. “Nothing small,” she says. “I want to do a big old fucking Greek play or Shakespeare,” whom she loves because of his rich female characters. “There is this really interesting thing in Shakespeare where women have this fascination with drag, male drag. It is very interesting to me that I’m talking about this thinking about Sally, who puts on Cliff’s suit at the end of [Cabaret]. There is a kind of masculine fascination, which is something that I have, that is kind of embedded in how I approach [the characters].” In other words, Rankin is ready for much more. “I’m certainly not downsizing,” she says. “Which is exciting. And terrifying. I’m tired as fuck.”

Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club is now running at the August Wilson Theatre, New York. House of the Dragon premieres on June 16 on HBO.

SHIRT by Helmut Lang. PANTS by Peter Do.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.