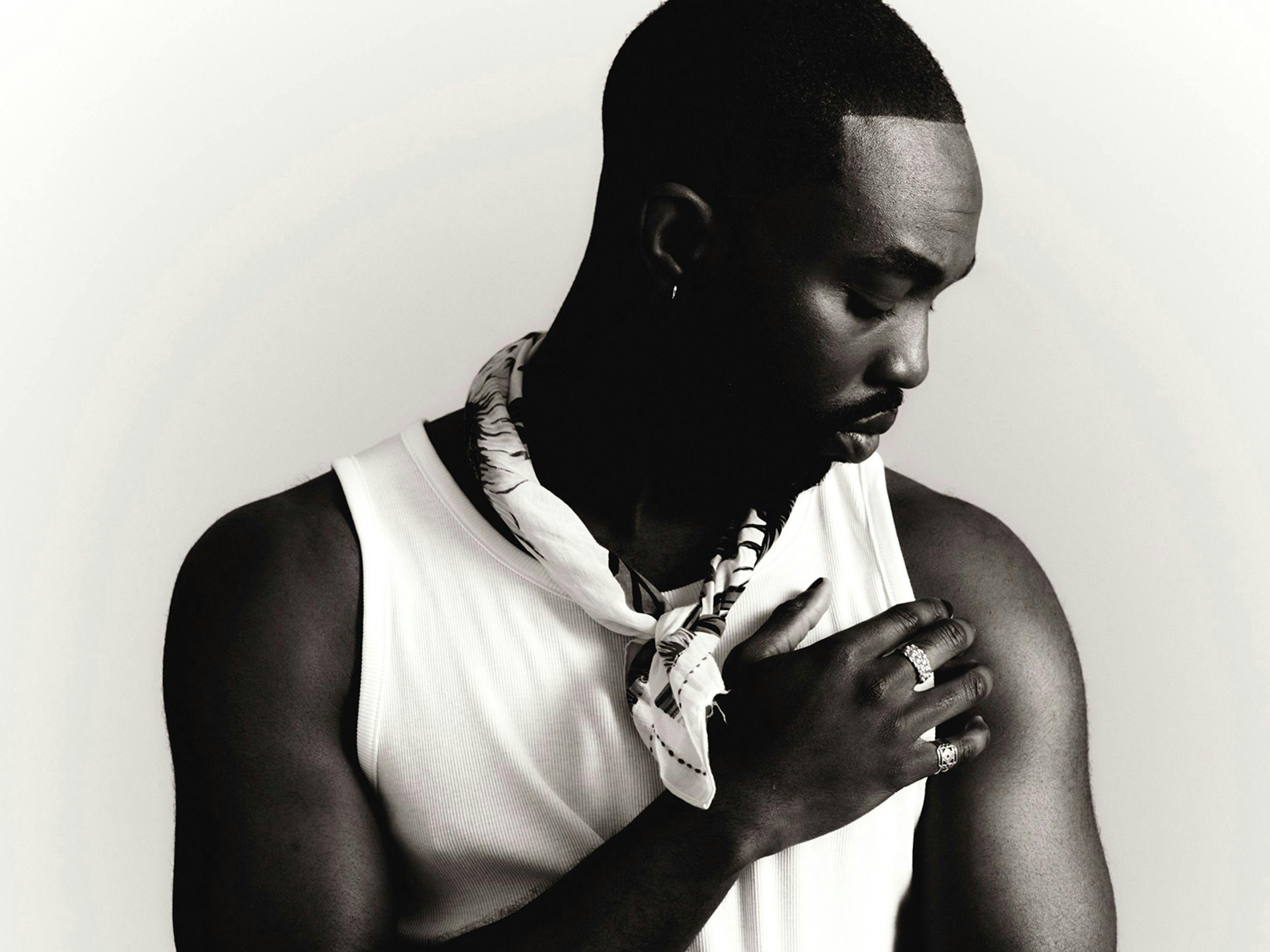

Jacket and sweater by Acne Studios. T-shirt by Gildan from Dave’s New York. All accessories, Ijames’s own.

Live from New York: James Ijames

Last May, the playwright James Ijames notched a historic—and hopefully unique—achievement when he won the Pulitzer Prize for a play that had not been performed live. In consideration of the widespread pandemic shutdown of theaters, the judging committee accepted digital productions, including Wilma Theater’s film of Ijames’s Fat Ham, which takes loose inspiration from Hamlet, reimagined around a Black family at a Southern barbecue, dragging the template of Shakespeare’s masterpiece into the modern age. Days after the announcement, the play opened at the Public Theater, and after a sold-out run, it is now playing on Broadway, where it was recently nominated for a Tony. “I loved the story,“ Ijames says about his initial centuries-old inspiration for Fat Ham. “It’s this play that is iconic in the theater. People call it the greatest play in the English language. I wanted to see if I could bring that play that I’d been so curious about for so long closer to my experience and have the characters from that play sound like me and look like me.“

Fat Ham’s Juicy, who stands in for Hamlet, is Black, queer, and unrestrainedly feisty, a far cry from the dour Prince of Denmark seen on countless stages. The rough structure of a son seeking revenge for the murder of his father remains, but tonally, linguistically, and æsthetically, Fat Ham strays far from its roots, offering raucous comedy in place of anguished tragedy. Ijames refers to the play as a “very, very loose adaptation,“ and notes that his intent was to interrogate the boundaries of a landmark in theater history. “At a certain point, the play leaves Hamlet, and the questions that Hamlet invoked continue on,“ he says. “About halfway through, the play stops being so rooted neatly into Hamlet and starts to ask questions and creates a narrative on its own moving forward, which is another thing I’m curious about—how can I mess with the structure of a play to get to an emotional depth that I’m looking to get to or to critique the source material? I’m curious about how form critiques the content and the content can critique the form.“

After watching his play as it transformed into a film and then back into a play, Ijames has come away from the experience with a newfound dedication to the practice of live performance. His plays, he says, should create friction with any adaptation to a different form. “I want to make something that demands, if someone wanted to make it into a film, they would have to really rethink the process of making a film in order to tell the story because the story needs to feel alive,“ he says. “When I’m working in the theater space, I want to be doing something that demands liveness, that demands real-time interaction.“

Besides his work as a playwright and director, Ijames served as the lead artistic director of the Wilma Theater in his current hometown of Philadelphia for the 2021-22 season. As a result, he has spent considerable time thinking about the larger landscape of American theater, even as he demurs when asked about his position in it as the only living Black writer with a play now on Broadway. “I try to think of myself and my work inside of a continuum, so I’m not individually superlative for any particular reason outside of that continuum of writers going all the way back to the beginning of Broadway, trying to find our way in that space,“ he says. “The thing that I hope comes from this is that I leave the place better than I found it—in this case, a Broadway-scale production with Broadway-scale visibility. I’m doing everything I can to add to that continuum of making the place more inclusive, more rich with diversity, more equitable in its practices and policies.“

Fat Ham continues through June 25 at the American Airlines Theatre, New York. Read this story and many more in print by ordering our sixth issue here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

All clothing by Acne Studios

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.