All CLOTHING and SHOES by Maison Margiela. All EARRINGS throughout, Jacobson’s own.

The Season of Louisa Jacobson

Louisa Jacobson describes her life as a series of oscillations—“full on and then full off”—a rhythm familiar to actors but disorienting to most. When the work is on, she is consumed: long rehearsal days, costume fittings, cameras waiting for her to deliver a moment that may or may not survive the edit. When the work is off, she withdraws, trying to resist the pull of “doom scrolling” and instead returning to small rituals that keep her imagination alive: reading, watching strangers on the subway, noticing patterns in how people move or speak. These cycles, she suggests, are not interruptions but essential; the silences and the stillness are part of the job, the place where she does “silent work that no one sees,” and the more she embraces that, the more prepared she feels when the next role comes.

There is, in the way Jacobson talks about acting, a persistent belief that the work is at once delicate and durable, that performance is a kind of truth-finding carried out under changing conditions, and that the real labor often happens away from cameras and crowds. The quiet credo sits behind almost everything else she describes—the craft choices, the advocacy on a set, the decisions about where to show up in public and why—and it gives her sentences a plainspoken steadiness, even when the subjects are charged.

When Jacobson talks about process, she starts at the level of medium, because theater and camera work don’t answer to the same rhythms. “My process is very specific when it comes to theater. [I] use Stanislavski method, the five questions,” she explains, referring to an early-twentieth-century system of acting devoted to embodying a character through the act of experiencing a character. Filming is another creature entirely. “On screen, you’re creating these tiny little moments out of order that will be pieced together by someone else,” and a script, she says, often gives you “the A’s and B’s and your job is to fill in the C’s. It’s all the unspoken behavioral stuff that is, I would say, smaller, not in the size of its truth but smaller in its expression.” The distinction isn’t academic—it maps onto the two poles of her current work life, the macro expression of the stage and the micro tuning of television, the actor who controls her performance “from start to finish” versus the actor who must trust an edit.

All CLOTHING by Khaite

That tension—between size and specificity, control and curation—shapes her portrait of two characters who could hardly be more different. On one end is Marian Brook of the HBO series The Gilded Age, a young woman “trying to create a path forward that is her own and not determined by the constraints of society,” even as she moves within those very constraints; on the other end is Jared in the recent off-Broadway play Trophy Boys, “so big! so campy! so draggy!” performed in drag as a teenage boy whose bluster is both costume and armor. Jacobson is interested less in the contrast than in the mirror they hold up to each other: with Jared, “the challenge is to find the dropped-in truth of those moments in order for the size to work and not feel like empty,” while “the goal for Marian is sort of the opposite—how can I take this small, tight, constrained thing and find the expansiveness within the constraints of this box?” For an audience, the result reads as range; for the actor, it is a single practice carried out at two scales—screen and stage.

Her latest stage role arrived the old-fashioned way—“my theater agent sent me the script and I really liked it”—and by a bit of serendipity: she had told Bernie Telsey, the casting director of The Gilded Age and a co-founder at MCC Theater, that she “really wanted to get back to the theater,” and when he mentioned a play she might be right for, she already had the script “in my inbox.” Loving the script, she taped for Jared, went through two in-person callbacks, and landed the role. What drew her wasn’t just the play’s appetite for provocation but the latitude it gave her as an actor: it would “allow me to do things that I never really get to do on screen.” That appetite—to stretch, to test, to bump into the boundaries of scale—also explains why, after the run finished last month, she wanted to keep limber; “once Trophy Boys closes, I’m going to take an acting class, I’ve got to keep it alive.”

All CLOTHING and SHOES by Gucci

Television, meanwhile, has been a terrain not only of performance but of persuasion. When she first received scripts for The Gilded Age, she saw how easily Marian might drift toward passivity—reacting to the choices of others, too quiet at the center of her own story—and she didn’t let that pass. “I wrote a very extensive letter asking for more from Marian,” she announces, seeking “complexity,” “more of her voice,” a resistance to the confines of a part that felt “quite small to begin with.” The request wasn’t an abstract demand for agency; it was tethered to specific turns in the story, like Marian’s relationship with her suitor Larry—“if we’re positioning her as a modern woman, then I think that we need a little bit more explanation as to why she becomes very rigid” there—and to what allyship might actually look like in that world. When her cousin Oscar (played by Blake Ritson) nearly outs himself in grief, she steps in to derail his behavior because she has the awareness and compassion to comprehend the dangers surrounding queerness in that period. Jacobson pushed for the intimacy of that dynamic to surface. “If Oscar were to reveal himself to anyone, it would probably be Marian,” she argues. “Outside of her own personal relationships, she’s very understanding and doesn’t judge a book by its cover. She’s very openhearted.” The touching scene that resulted—“I am so proud of” it, she beams—was for her “an example of an ally,” not in speechifying but in the trust of what one person will and won’t allow another to risk.

Jacobson’s advocacy runs parallel to an ethic she tries to bring to each new project. “If a piece is about a woman and if it’s not written by a woman, I want to make sure that the portrayal is fair, full, complex,” she insists. “That there’s room for me to be a collaborator—to add my voice to the process.” She doesn’t maintain a laminated list of rules—“you know what? No,” she laughs—but she does hold one principle close: “Remember that the truth has no size, and [as an actor] your job is to have a deep respect for the truth of human motivation: seeking the truth always.”

Her notion of truth has, in the past year, become more explicitly personal. Jacobson came out publicly “sort of late in life,” as she puts it—she is now thirty-four—and is building community deliberately, in small concentric circles rather than sudden immersion. “So far, I have a wine date and a coffee date coming up,” she says, smiling at the modesty of it. “I’m trying to expand my community. I have a lot of gay male friends already, but I want to grow my FLINTA [female, lesbian, intersex, trans, and agender] community!” There are parties she likes—“there’s a party called Ex’s that Mars [Castro] throws”—but mostly she returns to the tactile ordinary: “taking time to connect in person is important to me.” The point, for her, is not to narrate transformation but to live into it, to let belonging accumulate one conversation at a time.

LEFT: All CLOTHING by Miu Miu. RIGHT: All CLOTHING by Calvin Klein Collection.

Her public positions are spare and specific. Asked which organizations or advocates she’d like to uplift, she doesn’t hedge: “I love the Human Rights Campaign—what they do for the community, for LGBTQ+ youth through this horrible situation of having the Trevor Project ripped away,” she says. She praises fellow 2025 HRC Visibility Award recipient Hannah Einbinder for her climate advocacy and vocal support for a ceasefire in Gaza—”which I am also for,” Jacobson notes, understanding that visible people can redirect attention. The same measured approach guides how she navigates fashion and social media. She tries, she says, “to always have integrity with everything that I do. Even if it is branding myself, I try to have it be truthful to my intrinsic æsthetic—done with intention and not just because it would get a lot of eyes.” The temptations, she admits, are real—“we’re all out here trying to get work”—so she counterweights them by staying close to friends and “ground[ing] me back to my roots,” by joining spaces like the Actors Center, by keeping the craft at the core of her career.

She also thinks steadily about how to grow without losing shape. “When you start noticing that you’re hitting walls, it’s a sign of growth,” she says of a long run like Trophy Boys—the repetition is a teacher if you let it be—so the question becomes how to meet the new audience each night without resorting to habit: look “further into the corners and crevices,” figure out “what else I can be inspired by.” Sometimes that means turning away from the industry’s reflexive self-regard and toward people outside it; sometimes it means a small piece of found media, like a video that compiles students at an all-boys school as sixth-graders and then again as seniors, answering their former selves’ questions (“Do you have any advice for me?”), an artifact she returned to because it kept her from condescending to Jared, from “comment[ing] on him” rather than playing him. “I love the drive to be good and to be successful and achieve a lot,” she gushes. “It emotionally connects me to material that is otherwise very campy and draggy. Everyone deserves to have dreams and be happy. I have to ground myself in those things”—which is to say it restores the human scale inside the theatrical size.

Downtime is when the discipline is tested. The actor’s life, she notes, “makes it difficult for others around us.” Still, those stretches of quiet hold their own value. “You get these wonderful moments of stillness where you do silent work that no one sees,” Jacobson ponders. To do otherwise—to “doom scroll,” to “bed rot”—is, in her experience, to flatten imagination and “dim your cognitive ability to imagine and visualize.” As a result, she gives herself assignments: nourishing her body, working out, catching up on the series she missed when rehearsal swallowed her, saying yes to friends. The replenishment isn’t only artistic; it is also a way to keep scale in check, so that the rush of a premiere or a gleaming review doesn’t distort her habits of attention.

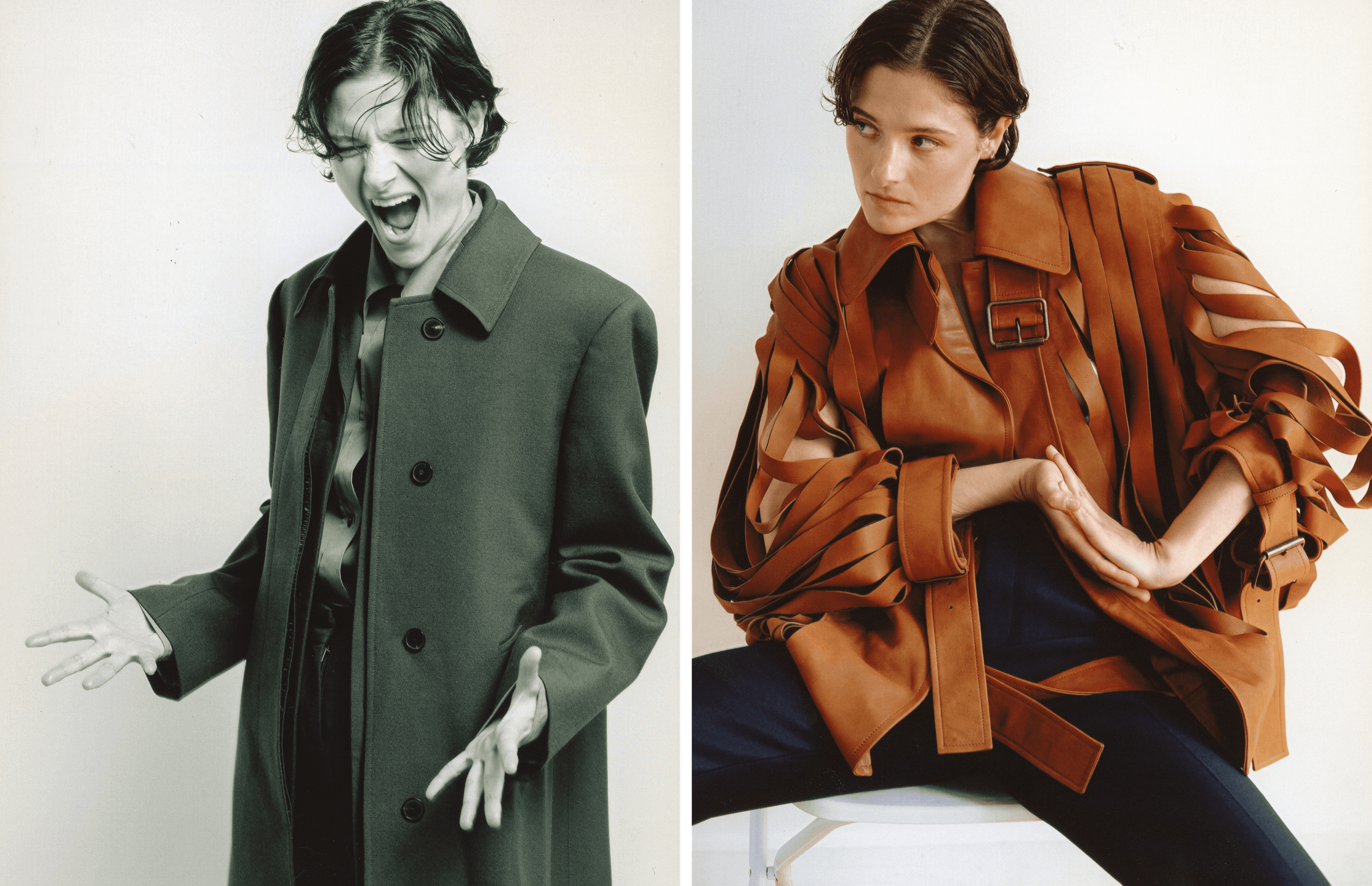

All CLOTHING by Loewe

Jacobson’s habits were shaped, in part, by an education in collaboration which traced a similar arc to that of her mother, Meryl Streep. At Vassar, where she “chose to major in psychology—true liberal arts,” she and friends staged guerrilla pieces—plays a classmate wrote, performed in physics lecture halls or off-campus houses—where she rediscovered the pleasures of comedy. “I remember really, really enjoying embodying someone very quirky and making people laugh,” she reflects fondly. “It’s the best!” At Yale School of Drama, she threw herself into the cross-disciplinary shop of the place—playwrights, directors, designers—and took from it something made clear by how she describes rehearsal rooms now: “you had to learn how to be a good collaborator in the theater.” The lesson has been durable; last year she assisted on Invasive Species, a friend’s play that moved “from The Tank to the Vineyard Theatre,” and she plans to keep shadowing directors. ”I never want to get comfortable,” she asserts.

If there is a through-line to the year, it is breadth. Onstage at MCC, she is Jared, swaggering and anxious and impossible to reduce; on television, she is Marian, making room for a character who might otherwise have been more observed than lived; on film, she’s stepped into Materialists, Celine Song’s new feature, where she appears as Charlotte in a brief but notable turn that rounds out a season spanning mediums. The range reads like a set of experiments in scale, a way of testing the same ethic—the truth has no size—inside different frames.

She doesn’t pretend the profession isn’t precarious. “Whether I like it or not, I see it as a series of choices,” Jacobson admits—tiny steps whose consequences are often unknowable in the moment; and in a world of pandemics, strikes, AI, and shifting audience habits, the arc can’t be charted with confidence. The answer, for now, is to keep moving at the level of the next meaningful choice. Over the next few years, she says, she would “love to create a project from start to finish and be in it. To self-produce or at least kickstart something and gather people around to make it even better.” Eventually, she aims to direct—first in theater, then see where it leads—because having “more of a hand in the story that I’m telling as an actor” is another way to be responsible for the truths she wants to hold on screen and stage.

LEFT: All CLOTHING by McQueen. RIGHT: All CLOTHING and TIE by Kallmeyer.

Even her style sense, she notes, has been nudged by collaboration. Watching costume designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone at work on The Gilded Age—choices of “color, pattern, texture,” bold yet “still true to the period”—has encouraged her to take slightly bigger chances beyond set. “I am pretty safe with what I wear. My stylist Edward [Bowleg] and I have a very collaborative process together, but we are both very safe,” she admits with a laugh. For the coming year, she wants to “take a little bit more risk.” “I love the sartorial direction that fashion is headed in womenswear—the androgyny of it all is very appealing to me as a queer person!”

It is tempting, writing about an actor in a season like this, to declare an arrival, but Jacobson keeps steering the conversation back to process, the unspectacular work that underwrites the visible peaks. She likes to be reminded that “the audience is new every night” and to hold on to the idea that hitting a wall is an invitation to search, not a signal to stop. The same stamina guides her life offstage—building a queer community one coffee at a time, showing up for causes she admires without making the attention about herself, saying yes to the class that will keep her alert. The mask of Jared’s masculinity—so comically inflated, so clearly a performance—becomes, in her hands, a way to talk about fragility without ridicule; the corset of Marian’s world—so tight it could muffle a person—becomes a test case for how much interiority can be expressed inside the smallest gesture. The point, Jacobson keeps suggesting, is not to choose between size and subtlety but to bring the same respect for motivation to both, the same “deep respect for the truth,” because that, for her, is the only rule that lasts.

And so Jacobson moves through this moment in a way that neither rushes nor delays. “Every time I go into a project, I ask, ‘Does this speak to me? Does it jump off the page and spark creativity in my mind, my body?’” Jacobson clarifies. “My one rule for myself in my work is to remember that the truth has no size. Don’t forget that it’s entertainment. You have to maintain a deep respect for the truth of human motivation. Seek the truth, always.”

The Gilded Age is now streaming on HBO Max.

LEFT: All CLOTHING by Calvin Klein Collection. RIGHT: All CLOTHING by Loewe.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.