SHIRT and JACKET by Tod’s. PANTS by Stella McCartney.

The Many Masks of Melissa Barrera

Melissa Barrera finds enjoyment in performing the “psychotic.” Not in a clinical or derogatory sense, necessarily, but in the specific, shivering thrill of the switch—the precise moment a person flickers between a performative warmth and a cold, calculating reality. It is a mechanism she has been toying with in her latest role, one that requires her to operate in a state of constant, fluid identity, where the mask is not just a tool but a survival necessity. Seated on a Manhattan street for a video call, she speaks about navigating such oscillation with the technical precision of a surgeon and the infectious enthusiasm of a true genre devotee.

She is discussing Michelle, her character in Peacock’s new espionage thriller The Copenhagen Test opposite Simu Liu, a role that functions as a complex nesting doll of deceptions. On the surface, Michelle is a spy embedded in the life of an intelligence analyst, but the performance requires Barrera to play a woman who is, herself, constantly performing to curb suspicion. “Basically, she’s a spy, but she’s an actor,” Barrera explains, drawing a direct line between the tradecraft of intelligence and that of the stage. “She’s embodying these different personas, which is what we actors do when we prepare for a role. So, I feel like being an actor kind of prepped me for that.”

“I wanted to play up the psychopathy a little bit because I just think it’s fun,” Barrera adds, her eyes brightening as she describes the sensation of watching a character toggle her humanity on and off. “I think it’s fun when you see people do that—it chills me but in an exciting way. It thrills me and it chills me.” In the context of The Copenhagen Test, this isn’t just about shock or entertainment value; it’s about the craftsmanship of deception, the ability to project a soul that isn’t there—or perhaps, a soul that has been buried so deep it only emerges in the jagged edges of a lie.

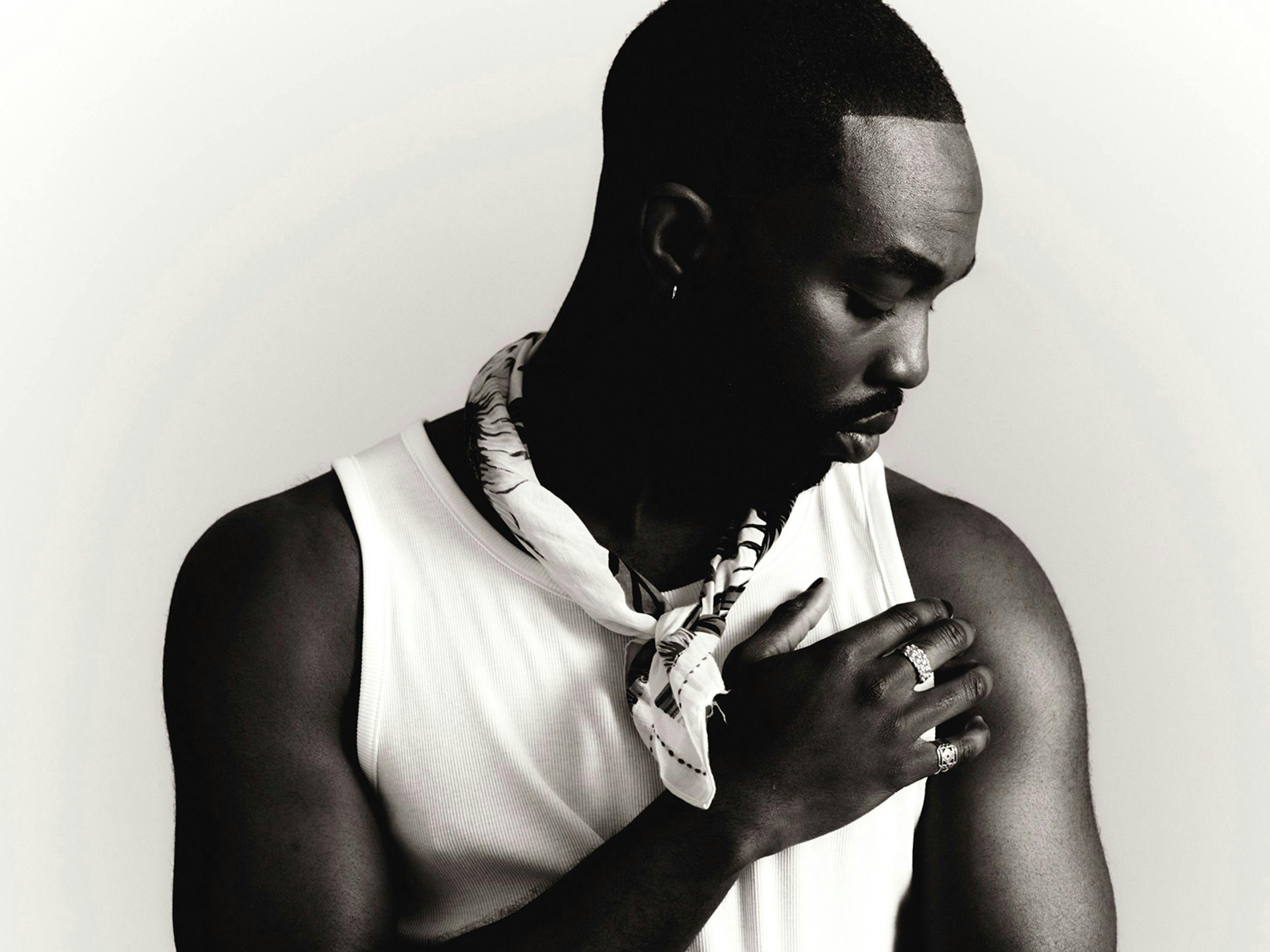

All CLOTHING and SHOES by Tory Burch

This meta-textual layering is the central tension of her current work. Barrera has spent the last decade moving through genres with the agility of a dancer—from the rigorous, high-stakes training ground of Mexican telenovelas to the sun-drenched, communal musical numbers of In the Heights, and into a streak of visceral, blood-spattered horror. But The Copenhagen Test presented a specific challenge of opacity. Her loyalties are so obscure, and there are so many different aliases that she is essentially multiple characters in one. Barrera admits the shoot was uniquely “challenging” because she was often kept in the dark by the show’s own architects, mirroring the very paranoia her character inhabits.

“It was hard to prepare for a character like that because I never had the information that I needed, and every episode they kept changing it up on me,” she notes, describing a process less like acting than high-stakes improvisation. “When I signed on, I didn’t know what it was going to be. I had just read the first two episodes, so it kept me on my toes.” To navigate this narrative fog, Barrera had to devise her own internal barometer for truth, a way to anchor Michelle even when the script refused to. She decided to gauge her performance by Michelle’s displays of emotion, because—in Barrera’s own words— “she’s not a very warm person.” The real Michelle is cold, efficient, perhaps even a little hollow; the spy, however, “plays up that warmth and that personality that feels like she’s looking into your soul and you can trust her.” It is a calibrated seduction, a weaponized empathy designed to make her a person “that would be very easy to connect with,” even as she is actively betraying that connection.

But Barrera is also keen on leaving crumbs for the audience—tiny, peculiar fissures in the mask that hint at the woman underneath. She recounts a brief, atmospheric scene set in a cemetery, which she describes as a “comfort spot” for her character—a detail that is never fully explained but suggests a long history of proximity to death. The script called for a simple phone call to her handler, Parker, establishing that her target still trusted her. Barrera, unsatisfied with a simple utilitarian scene, wanted more. “I was like, ‘Can we add one more layer?’” she recalls. She decided Michelle should be eating.

“I feel like eating in a cemetery is weird,” she says, noting that while the tradition of Día de los Muertos makes the act familiar to her Mexican heritage, in a general context, it feels unsettling. “And I was like, ’What’s the most psychotic thing that someone can be eating besides Vegemite?’” Her solution was a single packet of hot sauce. No chips, no meal—just the sauce, consumed like a shot of adrenaline. “That’s her snack,” Barrera muses with a grin. “Her threshold for pain is so shot—I wanted to illustrate that in a millisecond.” It is a blink-and-you-miss-it detail, inserted specifically for “the people that are paying attention,” a quiet signal that Michelle is a woman who has moved far beyond the standard human boundaries of comfort.

DRESS by Ila. TIGHTS by Falke. SHOES by Stella McCartney.

This attention to the mechanics of pain and endurance has translated physically as well. The role required a level of hand-to-hand combat that Barrera, despite her extensive background in dance, found unexpectedly humbling. “I thought that I was going to be good because I know how to dance and I can pick up choreography,” she admits, “but it’s a completely different beast.” The center of gravity is lower; the sharpness of the movement is distinct from the fluidity of a musical number. She spent her days off in Toronto training with the stunt team, demanding to learn the technique behind the punches before she even looked at the choreography, so she wouldn’t feel “like a fake” when the cameras finally rolled. Doing so enabled flexibility in the choreography as needed; if a shot required adjustment or an idea sprang to mind while blocking a scene, she could adapt without qualm.

“I love having to train for something. I love having to learn a new skill,” she affirms. Her hunger for competence extends to skills the camera never fully captures; she requested mixology lessons for scenes where her character bartends, even if the footage ended up on the cutting room floor. For Barrera, the research isn’t for the audience; it’s for her own sense of reality. “That’s for me, so that I feel like I’ve done my research. I’m going to feel I know this world that I’m in and I’m not going to feel like a fake.”

This dedication to “the truth” is the connective tissue in a broader body of work that is becoming increasingly eclectic. Whether she is fighting off a slasher villain, singing in Washington Heights, or, as she does in a recently shot horror/rom-com, “falling in love with a monster,” the approach remains the same. “The rule of thumb is to always find the truth,” she ponders. “I think if that’s your departure, your performance will be better for it and it’ll connect with an audience. Audiences can call bullshit, they can either believe you or not.” Even in the most heightened, satirical, or bloody genres, Barrera believes the emotional core must be unassailable. “Everything has to be from the soul of the character and from their truth.”

JACKET by Stella McCartney. SKIRT by The Andamane. SHOES by Simkhai.

Her next project, Black Tides, shot in the striking landscapes of Gran Canaria and Barcelona, focuses on a discussion around global environmental anxiety. Barrera describes it as a “disaster movie with a very strong emotional core,” centering on the unsettling (and very real) phenomenon of orcas attacking boats. “Nobody really knows why they’re doing that,” she notes, before offering her own verdict with characteristic directness. “I think it’s safe to say it’s because humans have been messing too much with the ocean. We’ve been taking too much. Nature fights back.”

The film, which features a small cast including John Travolta, allowed her to spend two months on and around the water, contemplating the relationship between human consumption and planetary reaction. It is a theme that resonates with her broader worldview, where art is not a separate, safe sphere but a direct participant in the political and environmental reality of the world it occupies. For Barrera, the act of storytelling is inseparable from the act of witnessing.

“I think art is inherently political. And I think artists should be activists,” she declares, rejecting the idea that her work exists in a vacuum. She is fully aware of the counterarguments, the cautious advisors who whisper about keeping things apolitical to avoid scaring off potential supporters or studio executives. Her response is blunt and uncompromising: “I don’t care about that. I know that the right people are going to support me. It’s very important for us to raise our voices—if you don’t stand for something, what’s the point?” She views the potential alienation of those who disagree with her values not as a professional risk, but as a necessary filtering mechanism; if someone is “so put off by your values, they probably weren’t the right person to work with anyway.”

She is specific and vocal in her advocacy, frequently using her platform to highlight the work of organizations like the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund and Operation Olive Branch, a nonprofit she admires for its “incredible work on the ground” in Gaza providing kitchens, tents, and essential resources. Closer to home, she speaks with passion about community-led neighborhood watch groups in the U.S. that organize to protect their residents from ICE raids. “It’s always the people showing up for the community when the government fails us,” she observes. “It gives me so much hope to see human beings that have lives and jobs and families putting their lives on the line protecting their communities. I find it so inspiring in a time that feels hopeless.”

All CLOTHING and SHOES by Tory Burch

After over ten years of work as an actor, a component in other creatives’ worldbuilding, she is now looking to take the reins and move beyond the role of the performer who waits for the phone to ring. Her definition of creative fulfillment has shifted from the short-term high of nailing a difficult scene to the long-term architecture of storytelling itself. “The most creatively fulfilled that I’ve felt in a while has been writing,” she reveals, describing the profound satisfaction of putting ideas to paper and building a project “from the ground up.”

Looking toward the next decade, Barrera envisions herself not just as a star but as an opportunity generator keen on creating space for others. “I hope in ten years I have a production company and I have a slate of projects,” she announces—her goal is to champion “aspirational, inspirational, hopeful, timely stories” and provide opportunities for new artists who share her belief that stories can be more than just entertainment. She wants to create work that has the potential to “change minds, change lives, and create an actual concrete change in the long run.”

It is a vision of the future that feels entirely consistent with the woman who inserts a packet of hot sauce into a scene just to reveal a character’s high threshold for pain. Barrera is done waiting for the script to be handed to her, relying on others’ whims to get in the room. She is ready to write the next episode herself—and this time, she’s the one calling the shots.

The Copenhagen Test is now streaming on Peacock.

All CLOTHING and SHOES by Hermès

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.