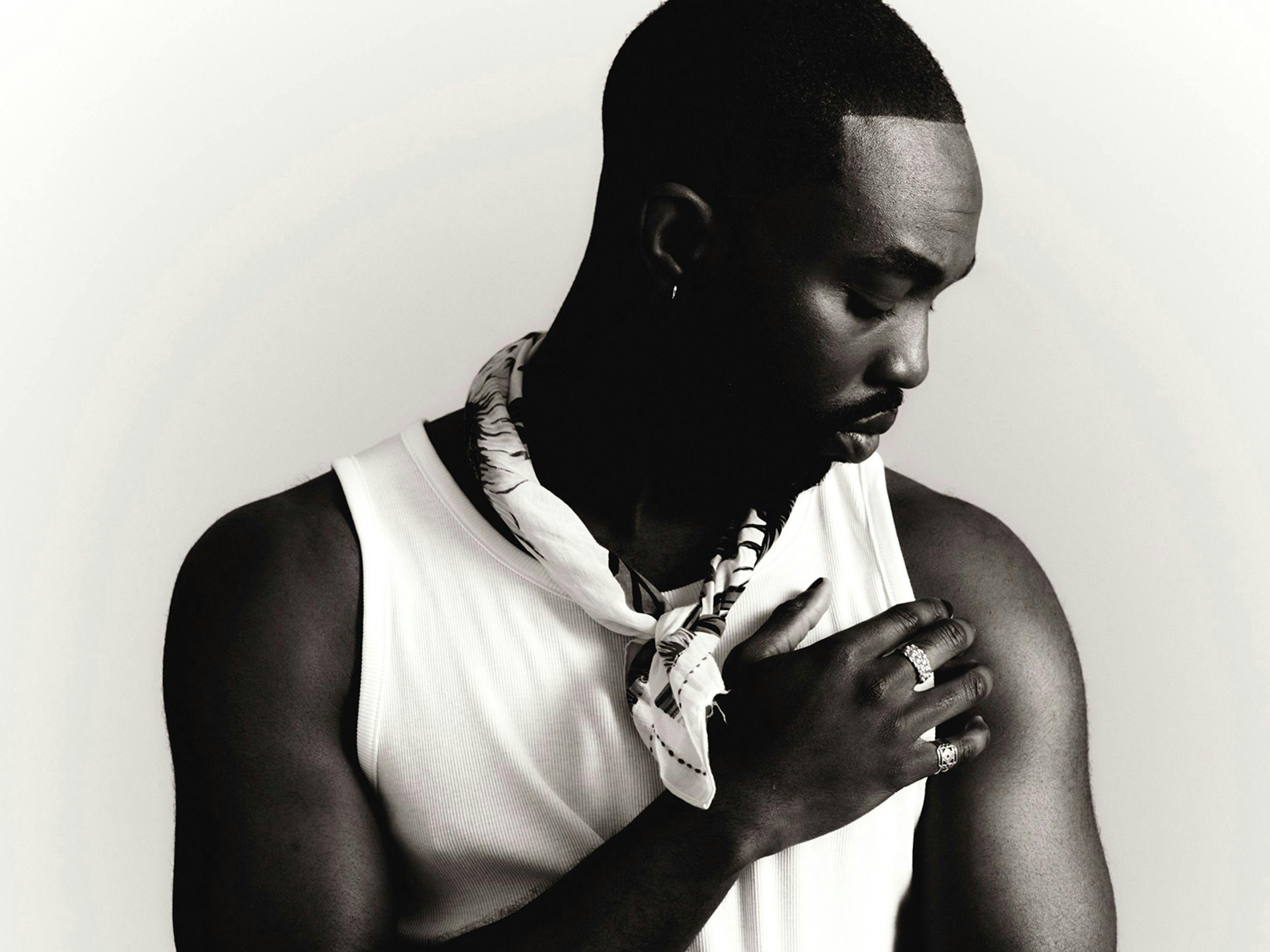

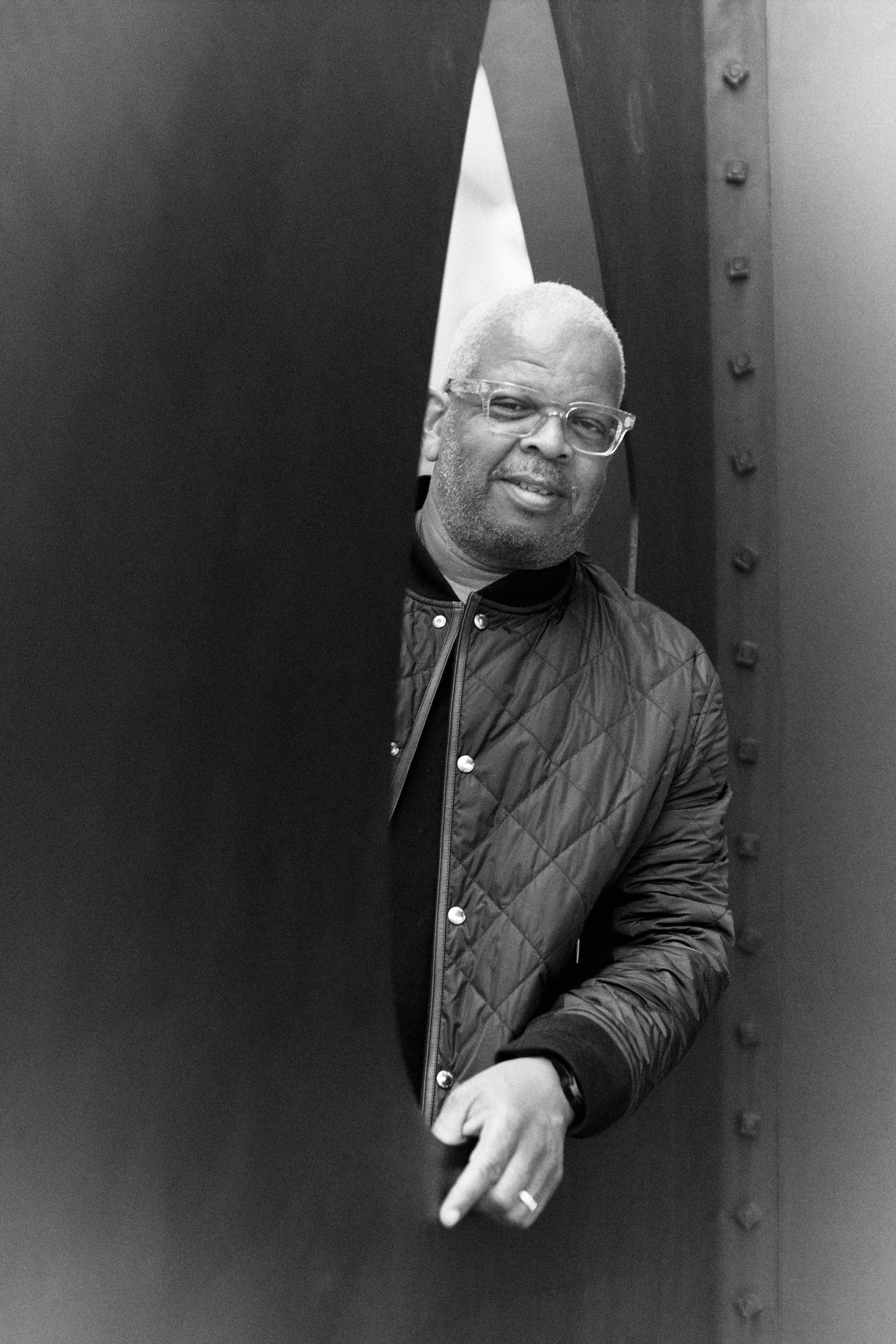

Live from New York: Terence Blanchard

Terence Blanchard and I are talking over the phone a few weeks after the premiere of his second opera, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, at the Metropolitan Opera House. We’re speaking about the influence of other art forms, such as painting and sculpture, on his own practice as a musician. “I’m fascinated by how there’s always a need to express something without words—people will always have a burning desire to communicate the intangible,“ he says. Like many of the kernels of wisdom he shares over the course of our interview, this one makes me pause. For a few moments, I consider the bigger picture of what it means for anyone to make art, to express their own intangible set of desires, memories, traumas, and hopes.

Blanchard is a six-time-Grammy-winning, world-renowned jazz trumpeter, bandleader, and Oscar-nominated film and opera composer. He joined his first orchestra as a teenager and has scored over forty films (Spike Lee is a frequent collaborator), recorded dozens of albums (his latest, Absence, was released in August and is an homage to the renowned jazz saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter), and written two genre-redefining operas. But Fire Shut Up in My Bones is more than a performance—it’s a historical event. Not only is the music a superlative combination of jazz, gospel, blues, and classical; the work also marks the first time an opera by a Black composer has been performed at the Met in its 138-year history. (Its co-director and choreographer Camille A. Brown is, additionally, the first Black artist to direct a mainstage Met production, and its librettist Kasi Lemmons is the first Black artist to write a libretto performed by the Met.) While Blanchard is deeply honored, he explains that he’s far from the first Black composer to be qualified for this distinction. The legendary composer William Grant Still, for example, submitted several operas to the Met over the course of his career, each of which was rejected. An internal submissions ledger went so far as to refer to Still—widely considered the “dean“ of African-American composers and the creator of nine operas, five symphonies, four ballets, and countless other works—as a “dilettante.“ The perennial rejection of brilliant artists of color by the Met has, hopefully, begun to come to an end.

Based on the 2014 memoir of the same name by New York Times columnist Charles Blow, Fire details the painful and emotionally fraught experiences of his youth in rural Louisiana (including the tragedy of sexual abuse) as well as a personal journey of self-realization and coming to terms with his sexuality. The opera’s evocative title comes from a passage in the Old Testament and speaks to the burden of not only of carrying a secret alone but also denying one’s desire for self-expression: “But his word was in mine heart as a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I was weary with forbearing, and I could not stay.“

The process Blanchard used to write the opera’s breathtaking music also emphasized the storytelling. He read the libretto and wrote it out by hand, speaking the words aloud. He jotted down the natural rhythms that arose as he read and transferred these to a piano, where he expanded on them. This remarkable method allowed the music “to reveal itself,“ he says, adding that “with an opera, there’s a story that has to be told verbally, so that’s what starts to dictate the rhythm. The story itself will tell you which direction to go.“

*

As I settled into my orchestra seat at one performance, I realized that there were more people—and a greater diversity—in the audience than I’d ever seen before. I’d always enjoyed observing the crowds, from the season ticket-holders in the center parterre box to the tourists gazing up at the dazzling “Sputnik“ chandeliers. It wasn’t especially common to see anyone in between, and in one sense this isn’t surprising: Opera hasn’t felt all that representative of contemporary culture for a long time. But the usual homogeneity was no longer present, as Fire had made the opera more accessible and more relevant to more people than possibly ever before. There was an electric current in the air, and it was impossible not to feel that you were about to witness something powerfully important on the stage. The diversity in the audience was part of this, and a thought started forming in my mind: Why is it important that we tell stories, and why is it important that we hear them?

Notwithstanding the fact that we can feel a meaningful affinity with a story whether or not we see ourselves reflected in it, our sense of self is the sum of the stories we are told, or tell ourselves, about who we are. We are inherently narrative beings: We need stories in order to survive. When we are denied the experience of both expressing our own individual narratives and witnessing them, we are denied one of the most fundamental tools we have to understand ourselves and the world around us. The Met isn’t the only space where the stories of opera are told and heard, but there is an undeniable symbolic power to its place within the operatic tradition (at least in the United States) when it begins to generate a far more inclusive vision of which stories get prioritized. “The biggest thing that makes me proud is that there’s so many young African-American talents that are being exposed and seen in this production,“ Blanchard says. “They’ve been around for a while, and this production is allowing them to be seen by new audiences because there are a lot of people who are coming to the opera for the first time.“

Musical traditions are as much a part of how we tell stories as any other narrative medium, and Blanchard’s decision to incorporate R&B, gospel, and jazz into the music was far from a purely stylistic one. “I told the singers to bring back their heritage into this performance,“ he explains. This was especially important because the vast majority of roles that opera singers perform are largely defined by white, European traditions, both narratively and stylistically. The baritone Will Liverman, who plays Charles as a young man, stated in a radio interview, “I’d never played a role where I saw so much of myself and my own story in it.“

*

Towards the end of our interview, Blanchard brings up another brilliant yet overlooked point with regard to the importance of telling our own stories. “What I’ve learned from teaching is that we all have a desire to say something, a need to say something,“ he explains. “Just because you may not have a talent for writing music—and this is the thing I tell my students—doesn’t mean that you have nothing to say.“ The medium, in this case, isn’t the message; it’s the authoring itself that counts.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones screens today in the Metropolitan Opera’s Live in HD series. Read this story and many more in print by preordering our third issue here. See the full Live in New York series here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.