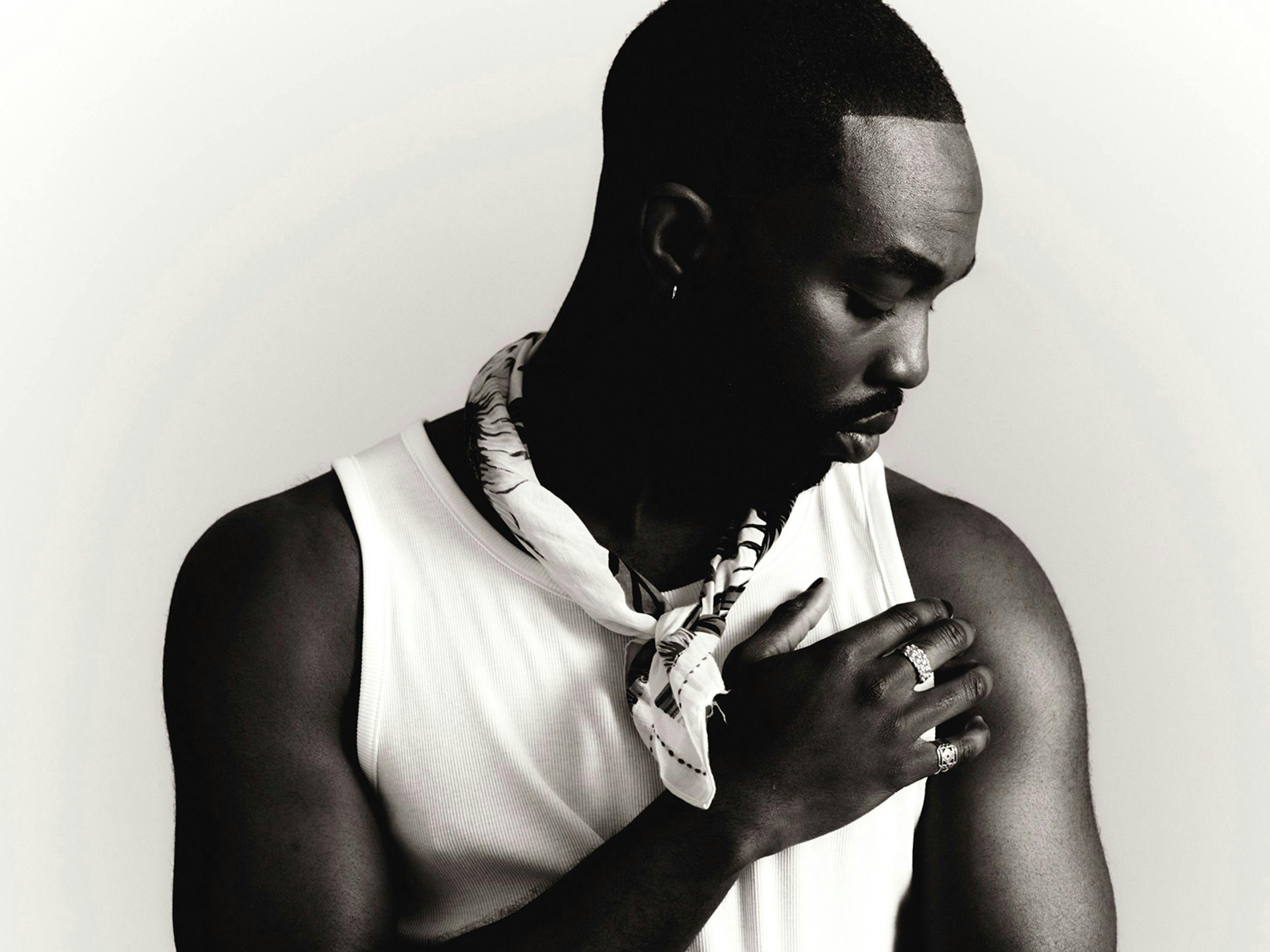

JACKET by Gucci

Tyler James Williams Grows in Front of and Behind the Camera

Tyler James Williams has been working as an actor long enough that the industry no longer feels abstract to him. He grew up inside it, learned how it can fail people early, and figured out—often quietly—how to stay intact. That history is evident in how he speaks about the work: plainly, without nostalgia, and with a careful sense of scale. Success is something he acknowledges, but it is not the organizing principle of his thinking—he prioritizes a sense of responsibility for the craft and centers the working environment he inhabits. Known to younger viewers primarily as Gregory from ABC’s smash-hit Abbott Elementary—created and written by trailblazing comedian Quinta Brunson and nominated for thirty Primetime Emmy Awards over the course of five seasons so far—Williams first came to national prominence as the lead of Everybody Hates Chris, a role that required him to carry a similarly lauded network sitcom while still a teenager. Before that, he worked on Sesame Street, entering the industry at eight years old through a system designed, at least nominally, to protect children. Even so, by the time he came of age professionally, he understood that longevity would require something more deliberate than momentum—a notion that would resurface years later during a period of unexpected quiet.

Williams began to shift into directing and producing during the pandemic, coming off an eclectic spree of roles in police procedurals and network sitcoms (as well as a notable performance in Dear White People) and a film shoot in 2019. “I just finished a movie in December of 2019,” he notes, “and I was looking for something to help me shake that.” When lockdowns began a few months later, the familiar structure of production disappeared; Williams responded by turning inward and outward at the same time. “I think I handled it the only way I knew how to—which was to get really creative,” he reflects. “[I] picked up a camera and started writing.” Rather than sudden clarity, the subsequent period entailed a long process of refinement that moved unevenly and required patience. “It’s a journey to figure out not only what your vision is and your style and your voice,” he reflects, “but to get to the place of being able to execute that.” The timeline mattered. “It took about five or six years,” he adds, before the ideas he began developing in 2020 were ready to materialize in a form that felt honest to him.

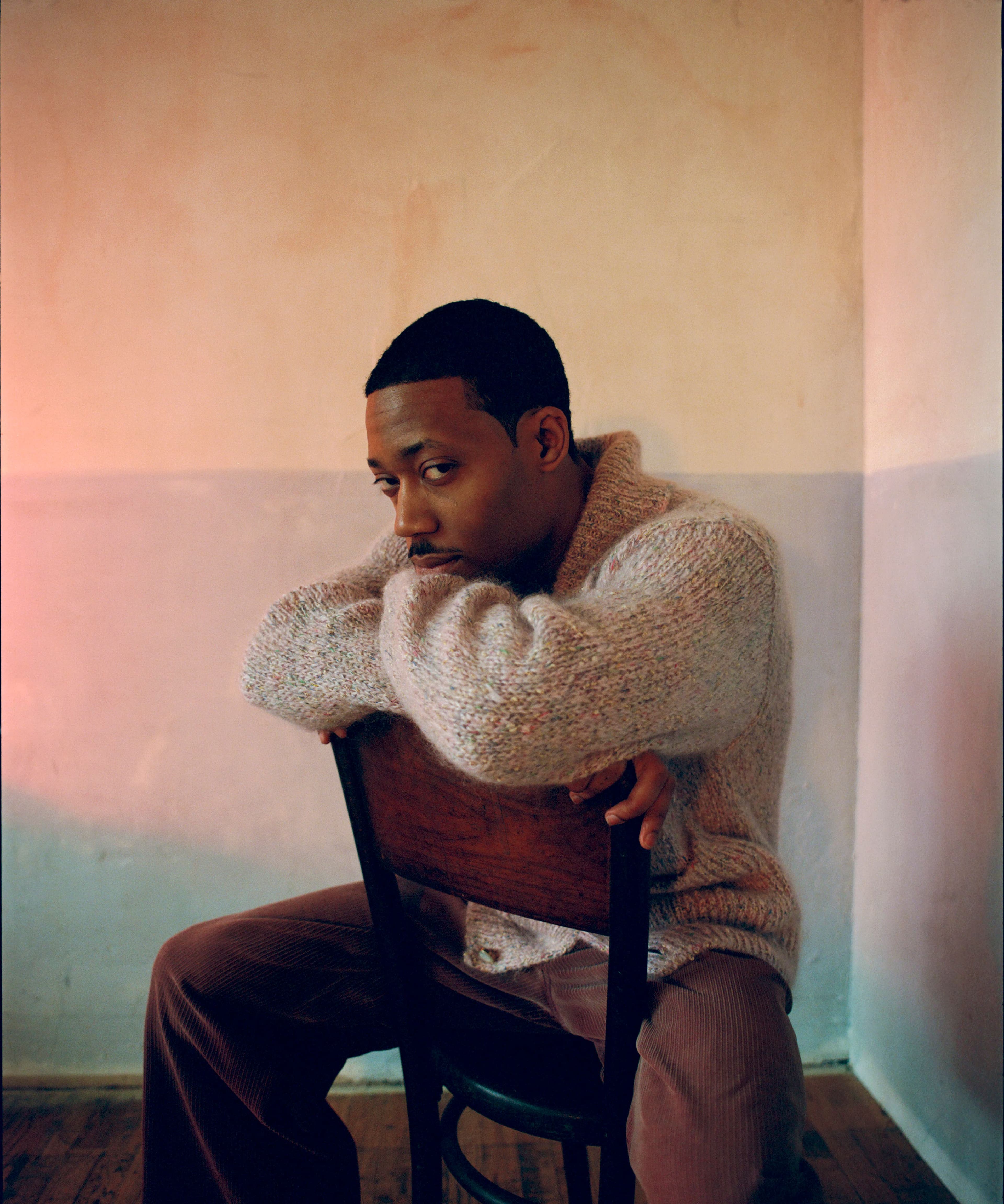

SWEATER by Dior. PANTS and SHOES by Hermès.

His patience now informs his work on Abbott Elementary, where Williams stars as the stoic and pragmatic first-grade teacher Gregory Eddie alongside a standout cast counting Brunson, Sheryl Lee Ralph, Lisa Ann Walters, Janelle James, Chris Perfetti, and William Stanford Davis as his colleagues. Lauded for its exploration of the pitfalls of the American educational system—underfunding, teacher burnout, predatory charter schools, and economic class tensions among them—Abbott Elementary has in many ways reinvigorated the American mockumentary sitcom format through its pertinent references to Internet youth culture while skirting the risk of overplaying its overtures to young viewers. Now in its fifth season, Williams has expanded his responsibility on the program through directorial contributions, for the first time last season and again earlier this month. His interest in directing comes less from a desire for control than from an interest in coordination. “I’m a big team guy,” he says. “I like how many people it takes to make something be good.” He pushes back against the idea of singular authorship. “There’s this weird ego thing that a lot of directors can have where they’re like, ‘It’s me.’ There’s no way that’s possible.” For Williams, directing involves clarity and responsiveness rather than assertion. “I think it’s rallying everybody to execute a vision that was in my head that ultimately serves all of us,” he asserts. What keeps him engaged is the need to communicate clearly and then listen. “There’s something about needing to articulate it and work with people and get their feedback on it that keeps me inspired.” Isolation, he notes, has never appealed to him. “Being able to work with other people at the top of their game? There’s nothing better than that.”

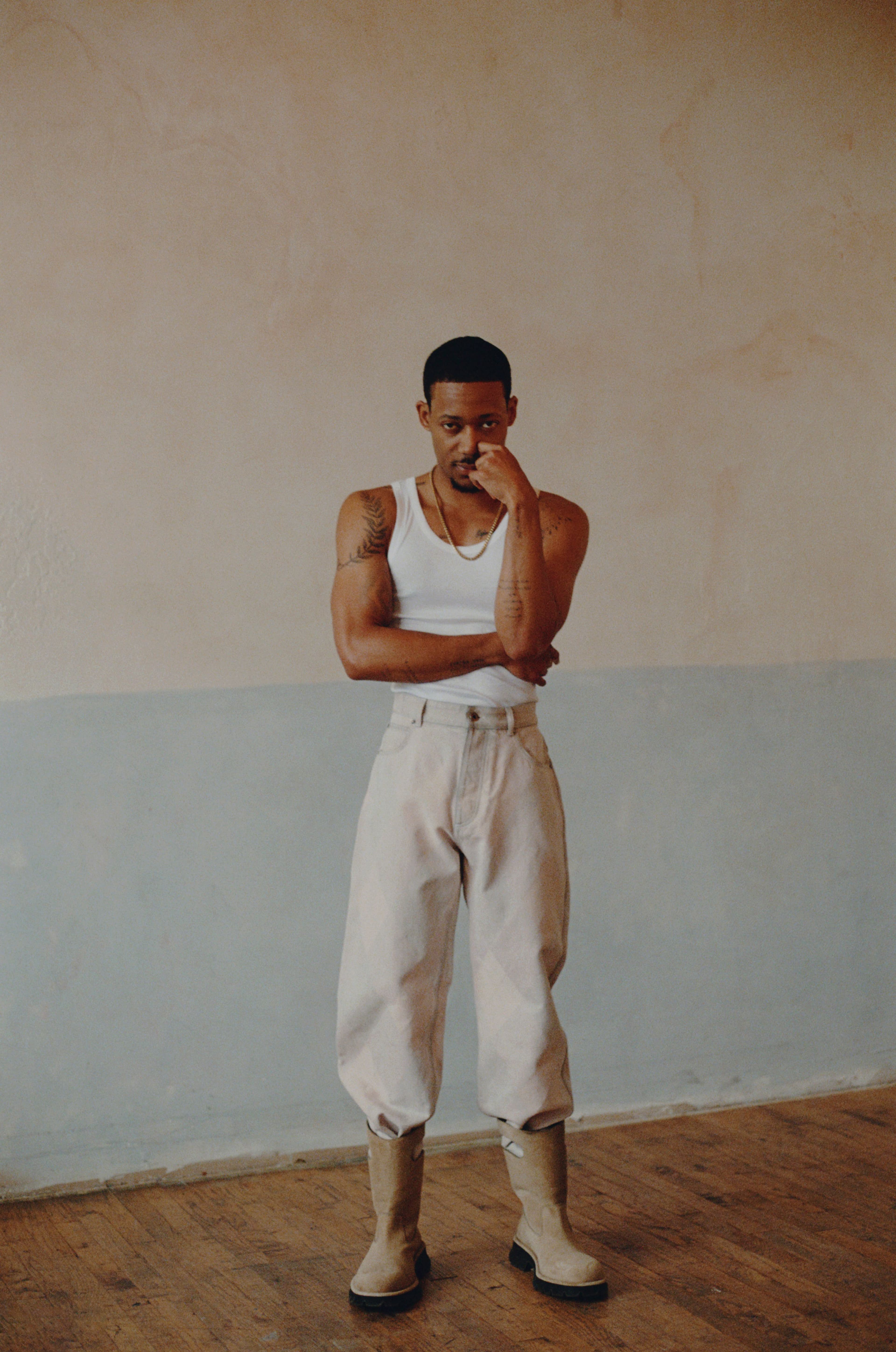

TOP by Hanro. PANTS and SHOES by Loewe. NECKLACE, worn throughout, talent’s own.

On Abbott, that collaboration is anchored by Randall Einhorn, the show’s executive producer and resident director, whom Williams describes as both technically authoritative and creatively restless. Einhorn’s background—spanning early reality television and The Office—makes him particularly fluent in the show’s visual language, but what Williams responds to most is Einhorn’s appetite for difficulty. Recalling a complex shot that traversed multiple spaces, Williams remembers sending the idea with hesitation. Einhorn’s reply was immediate: “That’s what makes it fun.” The validation was practical rather than flattering: yes, it’s hard, and yes, that’s the point. The ensemble nature of Abbott Elementary has become central to Williams’s thinking as well, especially as he has stepped behind the camera. The cast spans generations and career stages, and Williams is attentive to how that balance is maintained. “Everyone respects everyone’s position,” he declares, likening the dynamic to a championship basketball team.

That mutual respect, he believes, is what keeps the show elastic. “There are times where, like with Chris [Perfetti], I just have to let him cook,” Williams laughs. “Just give him a few takes to play, and he’s going to find some stuff in there.” Directing, in this context, often means recognizing when intervention would get in the way, an instinct sharpened by his own early experiences as a working child. “There’s no way it can’t,” he proclaims, when asked whether those years influence how he works with the child actors on Abbott. “My experiences growing up will forever texture the way I do everything.” Looking back on the early aughts, he identifies a cultural climate that was often unforgiving. “I think we realized that we were, at times, a much more mean society,” he says. “We look back on it and go, ‘Why did we do that like that?’” Williams situates his own generation as a hinge. Watching what happened to earlier child stars made certain dangers visible. “We were acutely aware of [what] happened to the previous generation,” he remembers, “and were actively trying to make sure [it] didn’t happen.”

SWEATER by Louis Vuitton. PANTS by Dior.

On Abbott, Williams tries to pass along that knowledge early and concretely. “I want to make sure that these kids understand from top to bottom what a set is, what everyone’s job is,” he affirms. When one young actor asked to shadow the script supervisor, his answer was immediate: “Yes, you one-hundred-percent can.” He wants them to see themselves as creatives beyond performance. “You’re a child, so no one’s going to let you direct anything,” he acknowledges, “but you are a creative already. There’s a lot of different ways you can do that.” His emphasis on education echoes a choice Williams made in his own teens, when he stepped away from steady acting work to train intensively. “I didn’t necessarily step back,” he corrects me amicably. “I actually stepped in.” He understood that turning eighteen meant competing with adults, and that familiarity could quickly become a liability—“I needed to stop, pivot, go deeper into the work, and then come back.” The shift changed how he approached everything. “I learned that a brilliant performance doesn’t happen by accident,” he recognizes. Preparation became nonnegotiable. “Everybody who’s ever worked with me, they know I’m a really serious human being. I’m going to prep the hell out of everything.”

What being an actor has taught him in directing, he says, is restraint. “If you overtalk actors, you’re now running out of time for them to calibrate their own instrument.” His notes aim for precision—sometimes a single word. “Indictment,” he recalls, as one that immediately unlocked a performance in the latest episode he directed. Just as important is freedom. “Here’s one where you can do whatever the fuck you want to do,” he tells actors. “Let me see what you got.” When Williams talks about fulfillment, he avoids abstractions. “I’ve tried to define this for years,” he continues to ponder. “It’s a feeling.” The sense of fulfillment and enjoyment of collaborative craft that he experiences when a scene finally comes together lingers. “You get home, and there’s this euphoric feeling of, ‘I just did good work.’” Money and recognition, he insists, are irrelevant without that. “If I leave work and I don’t have that feeling, I didn’t do good work today.”

TOP by Hanro. PANTS by Loewe.

The success of Abbott Elementary has intensified those dynamics. Awards and attention have followed, but Williams emphasizes the distinction between the show that airs and the one that the cast and crew experiences on set. “There will always be two shows,” he says, before reflecting on the skyrocketing success of the ensemble. The shared experience of acclaim can be destabilizing, he finds. “When there’s a spotlight put on you, there is an aspect of that which can be inherently traumatic.” The only people who fully understand that shift, he insists, are the ones standing next to you when it happens—cast and crew alike, bound by memories the audience never sees. Looking ahead, Williams is clear about his priorities. He plans to continue directing and is drawn to long-term creative partnerships. He points to Michael B. Jordan and Ryan Coogler as an example of what sustained collaboration can produce. “When two or three people get together,” he says, “the stuff that they make is a little bit different.”

Outside of his work, Williams has become an advocate for Crohn’s disease awareness after being diagnosed in 2016. “It almost killed me,” he puts it bluntly. His message is practical: take symptoms seriously, find a gastroenterologist, talk openly. “People suffer, man,” he maintains. He treats the advocacy not as branding, but as a responsibility, speaking openly and broadly with various outlets about his experience. This past fall, soon after three consecutive surgeries related to his diagnosis, Williams’ advocacy broadened through a recent and ongoing educational campaign with AbbVie dubbed “Beyond a Gut Feeling.” “I would encourage anybody to reach out and find a doctor for your gut,” he insists, before offering a starting point he has cultivated for those looking to learn more. “There are all types of resources on my pages and handles.”

JACKET and PANTS by Louis Vuitton. TOP by Hanro.

There is no sense of reinvention in his trajectory, only accumulation. “Somebody doesn’t just hit a game-winning shot one day. They were putting shots up in the gym for years and years and years and years and that’s why that dropped!” He reminds me. “This year I turned thirty-four and it will officially be thirty years I’ve been in the industry.” Across everything he does—acting, directing, mentoring, advocating—Williams returns to the same values: preparation, collaboration, community, and care. “If twenty years from now we have somebody up there winning an Oscar, going, ‘I learned how to do film and television from the set of Abbott Elementary,’ that’s it. I’m good after that,” Williams beams. “We got to pass the baton. That’s legacy. The world can go to hell.” He is not in a hurry to define his own legacy—he seems more interested in doing the work carefully enough that, years from now, someone else might say they learned how to do it by watching how he showed up.

Abbott Elementary continues on Thursdays on ABC.

TOP by Hanro. PANTS by Loewe.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.