You Got It, Take It Away

After talking to my father for over an hour—the dialogue meandering, banal, almost entirely one-sided—he passingly mentioned that my aunt and uncle had been crashing with him. My father lived in a community of people 55 and older, in a small trailer with many problems, so I found this news—which he’d muttered effortlessly, like using a horse hair as a brush to add a tiny detail to a painting—disturbing.

“No te preocupes,“ he told me; then in English, for flair, added: “Don’t worry about it,“ with the inflection of a movie gangster.

I pressed him for details, but he was vague. Before ending the conversation he said, as if I’d wrung it out of him, “Pues así están las cosas,“ then asked if I’d be watching the ballgame. He urged me not to stay indoors all the time, to go get drunk at a bar and watch the World Series.

I told him that’s what my problem was for many years, getting drunk at bars, which is why I stayed home now, but he didn’t find it as funny as I’d thought.

---

I ended up going to the old bar, caught some of the game, but was disappointed the jukebox was gone. They’d replaced it with one of those digital things that charged two dollars a song—but you could play any song—any song, eh?

I left the bar two beers in, unable to think of a single song I wanted to hear for two dollars. That night my neighbor was sitting outside his end of the duplex—from a little radio he played loud Cuban music, though he was white and understood no Spanish.

“Raf,“ he said. “I’ve been noticing your style. You always carry a big book. Surely you read them, too? Or are they just for self-defense? Kids around here, you know, don’t read.“

Lewis—my neighbor—was tipsy—possibly drunk. I recognized remnants of shooting insulin on a small tray next to him, and thought he must be diabetic, so drinking couldn’t be good for him.

Up in the sky was one of those moons that was supposed to be something special—like a blood moon, or solstice—but it just looked like a regular spider web moon to me. I wanted to get around Lewis as fast as possible, when he said, “Raf, I’m going to tell it to you straight. I don’t have long to live. I’ve done what I could for myself here, and with the money I make, my hospital bills, and rent, the future can’t be good. No way José I’m ever moving again, either—“

The ’no way José’ did it and I started walking past him. “Please. I want to show you something,“ he said, in a pleading tone that persuaded me.

“I have beers in the fridge, I’ll grab you one,“ he added.

In a flash I envisioned my dying days as an old man, just needing to talk to somebody after some beers. So I followed him in. Even though I knew Lewis was a jerk, and more than likely incorrigibly racist. Plus, I didn’t think to pick up any beer, and now I could keep my buzz going.

“I don’t recall mentioning it before,“ he said. “But my family is from New Mexico. New Mexico has an abnormal relationship with the sky, as you’ve probably heard.“

There are blues songs about living in a room so small it resembles a matchbox—and though our apartments were the same size, Lewis’s side managed to look just like that, with stacked shelves and tables of horded newspapers, VHS tapes, and tabloid magazines.

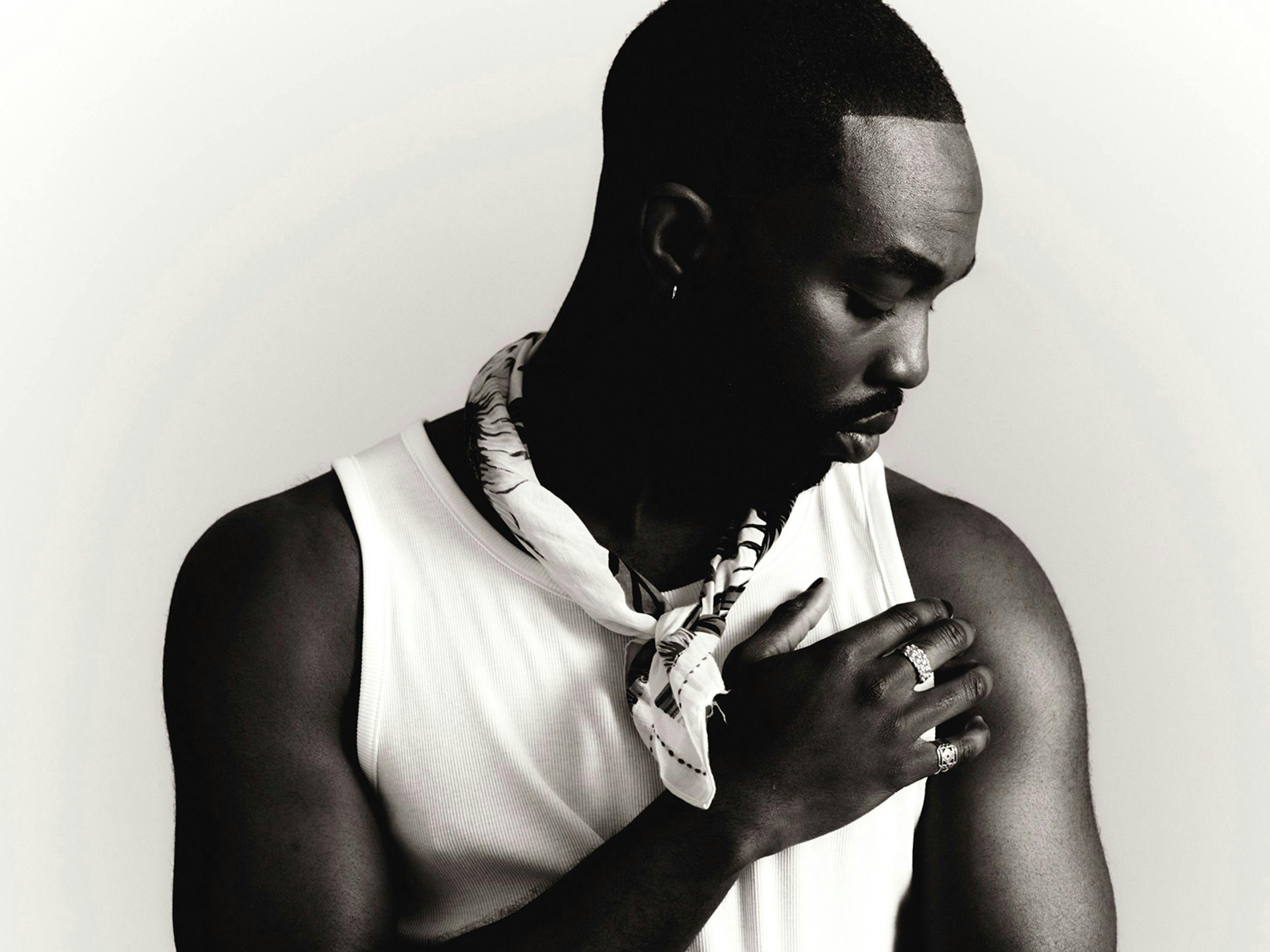

Clippings and cutouts about bank robberies and boxing matches and oil spills adorned various parts of the walls. Lewis brought out a framed, small photograph of a young woman and a man in a fancy suit.

“That’s my ma, with Harry Houdini,“ he said.

I don’t know why, but I laughed. This put Lewis off. He hastily hid the photo, frowning, and I feared I’d killed this moment. Lewis and I had been duplex neighbors now over two years. Aside from the time we got together to complain to the landlords about the plumbing, we had never exchanged more than a few sentences. We’d definitely never entered each other’s homes.

I heard sounds of rummaging coming from his bedroom. Neither of us talked for a good few minutes, and he must have turned off the radio, because the Cuban music that’d been so inviting was gone.

Lewis came out carrying an unmarked, smooth wooden box, with two hinges he thumbed to unlatch.

“People talk about Roswell like it’s the only big thing,“ he said. Lewis opened the box, took out and extended a thin, grey fabric that rippled like a liquid. It appeared both metallic and made of cloth. Lewis held it out and gestured in a way I knew he wanted me to feel it with my fingers. The material was cool, like finely woven chain mail, the way I always imagined chain mail to be in Arthurian sagas.

The fabric was just over the size of a handkerchief, and as Lewis held it by two corners the material continued to ripple like the surface of a pond in thin air.

“What is it,“ I asked.

Lewis put his left hand through the middle of the cloth. The cloth wrapped itself around his fingers and acted like an elbow-length glove. He extended his arm, showing how tightly the fabric wrapped, as if it was fit for him exclusively. It made his hand both shiny and transparent, depending on the angle.

Lewis said, “My old man. He was in the Air Force. His job one day was to go out and help recover a bad wreckage. Out in the desert.“

“Like aliens? Real aliens, from outer space?“

Lewis replied, “My old man. He took it nearly to the grave. We ended up finding it in a box after he passed.“

Lewis crumpled the cloth, tossed it to the ground, and it bounced like a tennis ball toward me, which I wasn’t expecting and nearly didn’t catch. The ball turned back into a liquid, grey cloth in my hands. Its texture was thin, nearly see-through—but if I tried to shape it, the material behaved more like aluminum. I folded it first into a cube, then a pyramid, and placed it on a newspaper stack on the coffee table, admiring its sturdiness. Then, upon grabbing it, the cloth seemed to anticipate this and went limp, back to its original texture. When held close to a light source it disappeared like smoke—then when held away again it lost its camouflage.

I folded it into an airplane, in a way I hadn’t done since I was a boy, and launched it over to Lewis. The cloth glided like the lightest papier-mâché.

Lewis handed me another beer, put the cloth back in the wooden box, and talked about his family and military service, without telling me more about the cloth. I knew the subject was long gone when he went on a rant about his disdain for Texas and Texans, then to prove it farther started singing a song about the sweetness Oklahoma.

As I got up to leave, Lewis looked at me with bloodshot eyes, and said, “Bandanas like those are what you wish. What you wish you and your homies could wear.“

Finding the comment more strange than insulting, I left him to his matchbox side of the duplex.

---

Meanwhile, my light bill hadn’t been paid in seven months. I’d received my final notice, did what everyone advised, and called to get on a payment plan, even though I knew that would accomplish little in getting the bill paid. But it kept the lights on temporarily and that’s what mattered.

In between the hustle of home and work, biking, riding the bus, and even when I’d wake up in the middle of the night, I couldn’t help but have one thing return to my mind: the liquid cloth belonging to Lewis. Once, taking a cigarette break during my shift, I caught myself pantomiming slipping the cloth on like a glove, in the same manner I saw Lewis do. I’d also called my father only once these past few weeks, and he was as chaotic and vague as ever about the state of his own affairs.

---

On my next day off I made the decisions to stay sober and to knock on Lewis’s door. I’d been thinking of the last thing he’d said to me before I left his place. His Chevy was parked on his driveway and was dirty with bird shit and leaves—like he hadn’t been driving it for days. I knocked again and said, “It’s me, Lewis, Rafael, your neighbor. You okay in there?“

“Come in,“ he yelled.

Lewis was watching a reality show on a tiny television that sat on a stack of tabloid magazines on the coffee table. He was reclined on one side of his couch, and had his right foot elevated at the opposite end, as if it pained him.

“My neighbor,“ he said, “from down south of the border.“

Lewis’s eyes looked redder than ever behind his small, rectangular glasses. I saw his balding, scabbed head with the evening light coming in through the kitchen window. I looked around for signs that he’d been drinking but didn’t see any bottles or cans anywhere. His place was piled more than before with TV Guides, completed crossword puzzle books, and gun magazines going back to the eighties.

“I’m from south of the border, but a citizen in this country now, Lewis. I can vote and have the same rights as you or any other fellow American.“

This made Lewis chuckle. I sensed he was feeling mean.

Preempting whatever response he might have had as he pointed one finger at me, I said, “Lewis, remember when you had me over a few weeks ago, and—“

“You were inside my house?“

“I mean. Yes.“

“How’d you get in?“

“You invited me in, Lewis, c’mon. You showed me your father’s cloth and everything.“

Lewis propped himself up, and his attitude became less menacing, more alert, perhaps cautious. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,“ he said.

A rush was going through me, and I got the same feeling I get when arguing with my GM at work. Lewis had been a displeasing presence in my life since I’d become his neighbor, and within a few weeks of living here I could see he resented the people living around him. Many times he’d called the police on the teenagers in the apartment complex next door who blared their hip-hop in the parking lot, and I’d heard other stories that’d given me pause. In short, Lewis had been on my shitlist on and off for the past couple years. But I also learned Lewis had severe medical problems, not only from diabetes, but also from complications after his ex-wife shot him and blew one kidney out. Though none of the neighbors knew the details of this incident, everyone unanimously, without asking, agreed Lewis must’ve done something to deserve it.

“Alright, Lewis, I said, trying not to stutter. “You had good music playing and invited me in, showed me pics of your ma and Houdini, showed off this cloth material, being all shady, telling me it’s from outer space and all that—“

“I oughta call the police on you. For going through my stuff. Get out of my house.“

“Okay, I’ll get out. I’ll never come back here, too. But last time when I left you told me something, Lewis. You said how I probably wished that cloth you showed me would be the bandana me and my homies could wear. I just want to point out that you live around many different types of brown and black folks here. Almost never do you see any of us wearing a bandana. How about that?“

“Get out of here,“ Lewis said. He reached for a crutch and got up. I was curious to see what he’d do, so I didn’t move. It was obvious Lewis was in bad shape.

He opened a drawer under his old radio, and, as if exerting a great amount of strength, pulled out a red baseball cap. Grinning, he dropped back down on the couch and put the cap with those four white embroidered words on his head.

I would have respected Lewis’s wishes the first time he told me to get out, but I sensed he was enjoying the tension, and now I knew why. This was his punchline.

The front door had been open this entire time, and he said, “You’re letting the flies in.“

“Whatever, Lewis. But I want you to know something. That I took an oath in a room with close to a thousand other people to defend the United States Constitution, and the founding principles of this country—“

“Bull-shit,“ he exclaimed. “I was born in this country, never had to take no oath.“

“That’s exactly right. You’ve never had to study the details of this country and what it supposedly stands for, and then have to take an oral exam about it—as an adult. Do you know how many people in congress there even are?“

“Over four hundred.“

“Who are our senators?“

He told me.

“What was the cause of the Civil War?“

He was about to reply then stopped himself, grinned, and pointed a finger at me again, this time in a you-almost-got-me-there kinda way.

“Anyway, this is where I’m getting at, Lewis. We have a sworn loyalty to this country, which in the end belongs to the people. You have that cloth made out of that fucked up material you said your father supposedly recovered from an alien spacecraft. And if you have information about it then you need to come out with it. Because the people need to know.“

Lewis was just staring at me under that red cap. Even I was surprised by what I’d said. Upon knocking on his door I didn’t imagine we’d come this far, flinging around words like spacecraft, constitution, and oath.

Then, on a whim—why not?—I took a risk, and said: “Give the cloth over to me, Lewis. I’ll keep it in the box and keep it safe. You don’t have any children, any heirs. I’ll make sure it gets into safe hands. Like we’re cowboys in a western and the frontier is all ours, and I’m making a promise to you in your deathbed. It’s one of those things like why we have the words ’faith’ and ’honor,’ and those beautiful string instruments are playing in the background in this scene. Please, just give the cloth over to me, Lewis. You can entrust to me that your great legacy will live on.“

In a voice that became deeper, lower, so that I knew he meant it, Lewis said: “Get the hell out of my household.“

It took all my energy to not throw him the finger as I walked back to my side of the duplex, where I blared old school hip-hop, making sure it reverberated all the way through the walls.

---

Since that exchange with Lewis I made it a point to enter the court of our duplex through the back alley, in order to avoid his door at the main entrance. Having bad blood with anyone doesn’t sit well with me; my instincts are always to reach out to the other person and try to make things right. In this case, however, I could see that nothing would ever get resolved by reaching out. Lewis was the person he was, and seemed to work hard at maintaining that persona. I didn’t have to befriend everyone in my life, even within the cheap places a lot of us are forced to live, close to each other, whether we like it or not.

What I did resent, however, was him keeping this liquid cloth to himself. Why should he hoard all that power? And what could this cloth actually be? I used various search engines and skimmed through every nonfiction book about Roswell and spacecraft wreckages I could find at the public library, with no success, until terms like “alien autopsy“ and “Hynek’s scale“ became part of my vernacular and I started freaking coworkers out.

I considered sharing all this with my father, since neighbor feuds and the supernatural were subjects he could relate to, but I never brought it up.

He did, however, fill me in on what had been going on, and his reasons for being so ambiguous about my aunt and uncle. It was no big secret within my family that my aunt and uncle had been in the country without papers going as far back as my childhood. So when he told me they were crashing with him I could only imagine the reasons why.

In recent years, even their most loyal previous employers had stopped giving them work, in large part due to the political climate. Horror stories had been circulating of workplace deportations. My aunt and uncle started talking about moving back to Mexico, and after a long deliberation, with support from the rest of the family, they sold their property and crashed with my father for just over a month as they made arrangements.

When I asked my father how he felt about harboring them he painted it as a somewhat emotionally taxing, but ultimately no big deal. “They’re over there now. We all gave our part in what had to be done,“ he told me. He laughed then said, “It’s like the película, con el, ’You got it, take it away.’“

“Cual película?“ I said. “Which movie? That’s from Johnny Canales’s show.“

Johnny Canales was the host of The Johnny Canales Show, a South Texas variety/musical Sunday morning program, famous during the eighties and nineties for showcasing Tejano and conjunto bands from Mexican communities around the country, and one of the first programs to have Selena y Los Dinos perform on television. He sat behind a desk not unlike Johnny Carson, wearing his trademark large glasses and flashy suits. “You got it, take it away,“ was his catchphrase—I couldn’t remember if he said it before cutting to commercials, after introducing an artist, at the end of his show, or all three. Growing up, Johnny Canales was always something of a joke between me and my grungy friends, but now as an adult I can see what an iconic legend the man was.

“No’mbre, cual Johnny Canales,“ my father said. “Es el Bogart, the actor in that movie. The woman who he was in love with comes back to his life asking him for help many years after he last saw her. Remember? The Nazis were after the man she had married. You know Bogart wishes things were different, and he could be together with her. But her husband needs papers to leave or they’ll be dead. Bogart gets his underground connections, even hoodlums he doesn’t know very well, to do their part in helping them leave before World War II. Ya, when they’re on the plane, Bogart turns to his friend, surely before going to get some beers to celebrate, y le dice: ’Amigo, you got it, take it away.’“

I was thoroughly entertained by this take and didn’t bother further contradicting my father’s memory. The more I thought about it, the more marvelous it became, and the more I laughed. My father had somehow conflated Johnny Canales’s catchphrase with the last line of Casablanca. I really, really wished for him to be right. For weeks after that phone call, during random moments, I’d picture Johnny Canales in glorious black and white, wearing that long trench coat and hat Bogart is famous for in Casablanca, emerging from the fog holding a pistol, ready to shoot a fascist.

It’d been years since I watched the movie, so I borrowed a small TV with a built-in VHS player, and rented it from the last video store in town. After watching the movie it became clearer than ever: Johnny Canales as the owner of The Blue Parrot, drowning his sorrows as he watches the tourists drink and gamble while all hell broke loose around the world; Johnny Canales reading that farewell letter in the heartbreaking rain; Johnny Canales, in what he knows is possibly his last chance, holding Ingrid Bergman, and really looking into her eyes to say those famous words.

I watched it while spending Christmas day alone, and this last image of Johnny Canales is what did it for me. This impossible idea of a screen legend like Ingrid Bergman having this tragic love with Johnny Canales, a Spanglish-speaking border ranchero turned Tejano, who styled himself and talked like any one of my uncles, was just too unbearable. It even made me remember my own lost loves and dead family members. With all the lights in my apartment off I had one of those good, heaving cries, where your insides tumble out and you don’t know who you are any more.

---

Boxing Day: a holiday we didn’t observe in America, though I always thought it to be the perfect way to describe a Christmas hangover. I decided to take a walk around the east side and find coffee, thinking of my aunt and uncle and my father. Again, I couldn’t help admire how my father’s immigrant memory juxtaposed those two bits of American pop culture. Even when I was young, and ignorant about cinema, I knew the last line of Casablanca—the real last line—was a cultural phenomenon within itself: “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.“ Spoken to an almost stranger, of course, after learning they could make a few bucks on the side while fighting fascists. It’s the last line you’d even wish for in the biopic of your own life, scheming as you walked away into the credits.

When I headed back to the duplex I noticed commotion coming from Lewis’s place. There was a moving truck and two young men carrying stuff out from the apartment; a trash bin sat on the curb brimming with the glossy magazines and old furniture I had seen in Lewis’s place.

The palms of my hands started sweating as I weighed for a second rushing in there to find that wooden box with the liquid cloth—that grey, sweet, metallic cloth I could never forget.

A group of kids were gathered in the parking lot across the street, blaring music, watching the men emptying Lewis’s place. One of them was a kid with the red Mohawk who I’d bought raffle tickets from before.

“This guy finally moved out?“ I said to the kid.

Another kid, sitting next to an upside down BMX bike, said, “Nah, he died.“

“What?“

“The ambulance took his body the other day,“ the kid with the red Mohawk said.

“No way.“

All the kids nodded. Though Lewis was in many ways the neighborhood antagonist, and it was the day after Christmas, they were all quite somber and displeased.

Much later, I found out through the landlords that Lewis suffered a heart attack from a gangrene infection on his foot that had spread in part because of his diabetes. It turned out he did have two sons he rarely talked to, and it was the two of them who were clearing out his apartment.

That day, standing next to the kids blasting their mix-tapes, it wasn’t lost on me how close Lewis’s name was to the name in the real last line of Casablanca. Lewis’s sons never acknowledged us, not even making eye contact once, as they loaded the truck.

I looked at the kids and said, “You got it, take it away,“ with behind-the-desk gestures and all—but there’s no way they could have gotten the reference.

---

Passing the courtyard entrance I established my presence enough so that both brothers made eye contact with me, and I gave them a sympathetic nod. When I decided to take a longer stroll I walked by my apartment, slipped through the back alley. Without looking back, as the kids zoomed the streets on their bikes, I said, loud enough for anybody to hear: “Lewis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.“

Read this story and many more in print by ordering CERO04 here

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.

As a nonprofit arts and culture publication dedicated to educating, inspiring, and uplifting creatives, Cero Magazine depends on your donations to create stories like these. Please support our work here.